Topic: Ending the Silencing

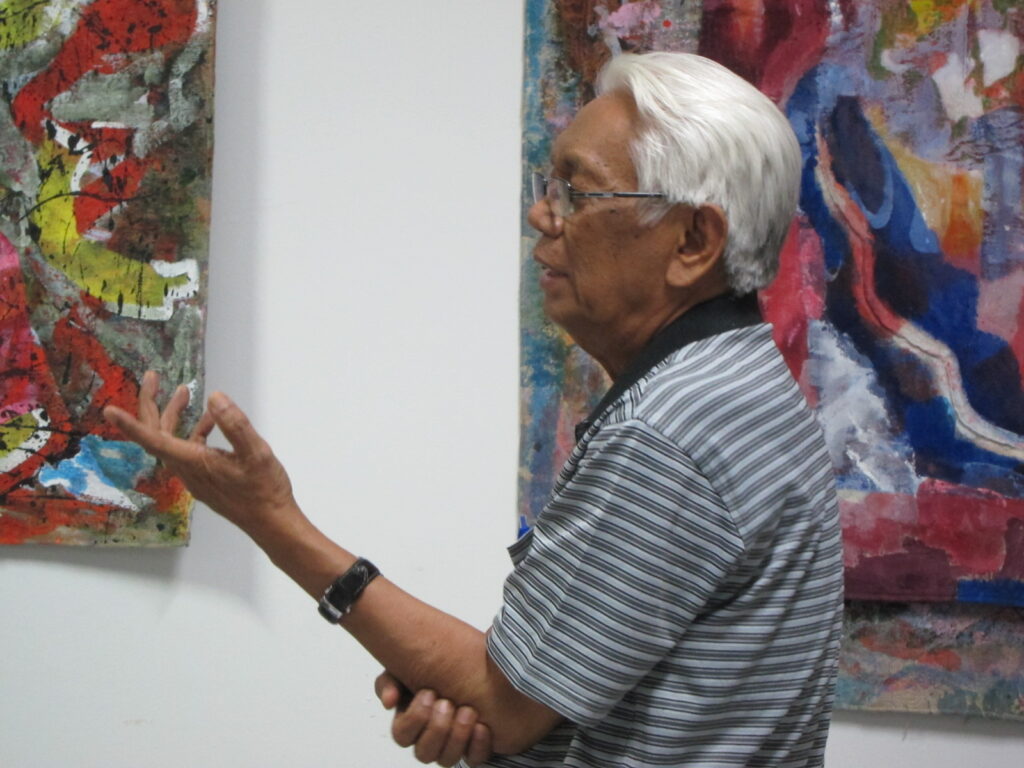

Speaker: Putu Oka Sukanta

Date: Tuesday, 5 November 2013

Time: 8:00 – 9:30 p.m.

Venue: Muse House, 22 Marshall Road, Singapore 424858

About the Speaker:

Putu Oka Sukanta, born in 1939, stands as one of Indonesia’s prominent literary figures. His journey into the world of writing commenced at the age of 16, a period marked by the tumultuous pages of Indonesian history. In 1966, he was subjected to detention and torture by authorities, a consequence of his writings and affiliation with Lekra, a left-leaning artists’ association.

Emerging from over a decade of incarceration in 1976, Putu Oka ventured into an acupuncturist career while maintaining his literary pursuits. His writings have echoed the experiences of former political prisoners who faced discrimination in employment opportunities. The post-Suharto era, commencing in 1998, allowed Putu Oka to share his works both within Indonesia and on the global stage. Notably, his literary portfolio extends to encompass traditional health, herbal medicine, acupuncture, and acupressure.

Collaborating with emerging Indonesian filmmakers, Putu Oka has brought to life six documentary films capturing the tumultuous events of 1965-66. His influence has reverberated across various countries, where he’s been invited as a guest lecturer, participating in seminars, readings, and study tours centered on literature and alternative health. This international outreach includes destinations like Australia, Malaysia, Thailand, Britain, Germany, Singapore, and the USA.

The significance of Putu Oka’s endeavors has been acknowledged through numerous awards. In 2012, he was honored with the Hellman/Hammett grant by Human Rights Watch in recognition of his courage in the face of persecution.

In this session, Putu Oka Sukanta will illuminate the power of breaking the chains of silence, offering insights into his personal journey as a writer, activist, and advocate for truth and justice.

Writing is media to struggle against dehumanization

Dehumanization process started when the militia and military started hunting and killing suspected communists in October 1965.

Writers and artists accused as members of Lekra, a cultural association, would be put in the prison or exiled if he was lucky enough not to be killed.

There was no protest to this mass killing from the West as well as Non-aligned Countries.

I was detained for 10 years without trial (1966-1976), and endured terrible conditions, malnutrition and diseases. I was terrorized mentally on a daily basis and prohibited from having a pencil or book throughout my imprisonment.

They moved me from prison in Jakarta to Tanggarang in West Java and back to Jakarta again. I was moved from small cells to the prison of my own country. I was subjected to discriminatory regulations set to dehumanise Ex-Tapols ( ex- political detainees) and their families (Instruction Education and Culture Ministry,No.138/1965, TAP MPRS no.25/1966, Internal Affairs Instruction 1981,no.30). The process of dehumanization works systematically and structurally.

As a writer, I use writing as a media to fight against the dehumanization process in order to be human again. The past is my backbone. In the beginning, some national newspapers accepted my writings, but later, I was barred because of political reasons. As a writer, I use peaceful ways to pursue my career. I won the Environment Story Teller award organized by Indonesian Government, and an international (NEMIS) short story competition organized by the Chilean Embassy in Jakarta. I was invited to International Popular Theatre Workshop in India, conducted regular literature readings in Goethe-Institute in Jakarta (the only public space for me), read my poems in universities in Australia, Malaysia and Europe, and published my works through alternative publishers. Some of my short stories and poems have been published in several international anthologies.

As an acupuncturist certified by the Department of Health, Indonesia, I started work with grassroots communities to increase their awareness of the rights and obligations in health, and shared my knowledge and skills of acupressure and herbal medicine.

For those activities, I had to pay a price too. The Soeharto regime detained me in July 1990 for ten days after a trip to West Germany organised by Goethe Institute. I was tortured with electrodes. They suspected that communist international organizations supported me. My health foundation and clinic were banned. But that never stopped me from working although the intelligence service strongly controlled my daily activities. The hard challenges forced me to work harder and harder. My life was tense and full of stress, but I continued to write, and was active as motivator and instructor of health, humanity, HIV/AIDS and gender equalization programs. My works in many fields have enriched my writing about the life of marginalized people. I have also made many new friends.

After the fall of Soeharto, military surveillance was visibly reduced. The first thing I did was to publish a novel “Merajut Harkat in 1999 which I started in 1979, as well as a compilation of poems “Perjalanan Penyair.” These books were inspired by my experiences in jail. The mass media took a sudden notice of my work: they were eager to discuss the books and know about me as a writer. Without any rest, I continued to write and publish health books. Since 5 years ago, I have worked with some friends to produce documentary films about the Tragedy of 1965/66 and its devastating impact on society. My human dignity is regained even though the discriminatory regulations still exist. As a writer, I continue to fight against the dehumanization process everywhere, produce films and involve myself in human rights issues.

They gave me. they gave me a lump of courage flowing through my veins they gave me a shaft of light shining within my eyes they gave me a glass of bile strengthening my every step they gave me a piece of stone which I crushed and made a road they gave me a whip witch tightened the muscles at the base of my tongue what else can you give me to test my self-respect? (from book The Song of Starling, 1986, translator Keith Foulcher)