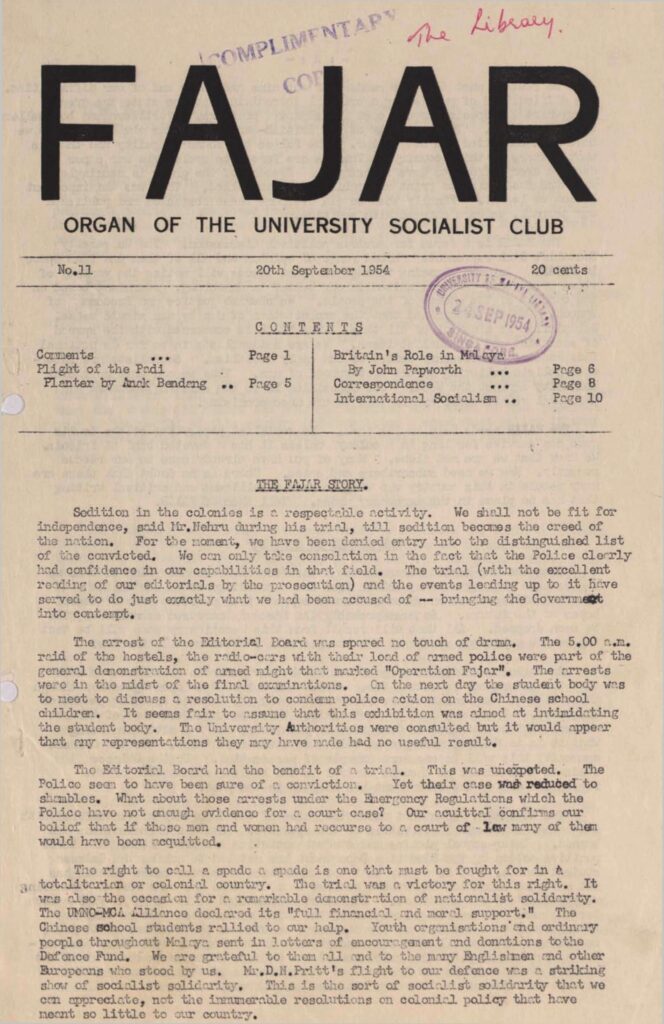

The Fajar Story in Fajar 20 Sep 1954 No.11

从华惹诉讼到华惹世代 – 傅树介(林康 译)

This year, 2024, marks the 70th anniversary of the editorial ‘Aggression in Asia’ in Fajar issue 7, 10 May 1954 which led to the arrest on 28 May of its editorial board members on the charge of sedition. As the president of University Socialist Club, the publisher of Fajar, I was one of the eight defendants, and the point man. I was then a 22-year old 3rd year medical student. Nine years later, at age 31, I was arrested and imprisoned without trial in Operation Coldstore. With a break from December 1973 to June 1976 when I was released on restriction orders, I was rearrested in 1976 and was released when I was 50 years old. At the age of 77, I was one of the editors of The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore (2010).

At 92 years old, I have this opportunity to commemorate the Fajar trial as a landmark in Singapore’s decolonization process.

The Fajar Trial

The Fajar trial changed the course of my life and must have those of my co-defendants as well. The event also altered the course of politics in Singapore which the British colonial rulers had been charting for post-war Singapore.

We had not set out to court arrest and make headlines with ‘Aggression in Asia’. In fact, we were careful to reference prominent British left wing Labour Party leaders in condemning the formation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) as the militarization of the region, evident in the ongoing war by France against Vietnamese anti-imperialism. We contended that Malaya was being turned into a military base for colonial wars which our young men were being conscripted to fight in.

We had no idea that on May 13, three days after the publication of ‘Aggression’ the Chinese middle school students would be attacked by the police for objecting to the registration of school students for national service. We stood with the students. The day before our arrests, the University student body had arranged a meeting to discuss a resolution to condemn the police action against the middle school students. (See ‘The Fajar Story’, no. 11, 20 Sept 1954).

With the Fajar trial and the May 13 police violence “Merdeka” became the most popular and powerful word in Singapore politics for the better part of a decade.

The arrest of University Socialist Club members on the charge of sedition i.e., inciting people to rebel against the authority of the Queen was sensational, but the dismissal of the case by the judge was even more so.

Our lawyer, D N Pritt, QC had represented anti-colonial leaders including Indian revolutionaries, Kenyan independence fighters, and Ho Chi Minh. John Eber, a senior lawyer and a key leader of the defunct Malayan Democratic Union (MDU) who moved to the UK following his release from detention in 1951 under the Emergency Regulations had approached two eminent lawyers to represent us. I went for Pritt, who duly got us to research on sedition cases in the British colonies from Amritsar to Batang Kali. He was going to turn the trial into a political event.

The Emergency and the Fajar Trial

I regard the left in the MDU as our predecessors in the anti-colonial movement. The party, founded following Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, was made up of English-speaking Malayans in Singapore who were opposed to re-colonisation by the British. The MDU attracted young lawyers, Raffles College graduates, clerks, as well as members of the MCP, which had been legalised after the war.

The political space that emerged in the MDU period did not last for long. A state of Emergency was imposed in June 1948. Once again listed as illegal, the MCP waged jungle warfare in the peninsula against the colonial military forces. In October 1949, the People’s Republic of China ruled by the Chinese Communist Party came into being. Repressive political action on the island followed in quick succession. In May 1950, the British managed to smash the Singapore Town Committee, which they alleged directed communist operations. The Chinese High School and Nanyang Girls’ High School were raided by the police and closed for two months with about twenty students arrested under the Emergency Regulations. In 1951, the left-wing MDU members including John Eber, and students of the University of Malaya were arrested. Following the repressive blitz against anticolonial groups, the government was ready to allow its protégés to assume political leadership in a controlled process of decolonisation.

The Rendel Commission was set up in 1953 to work out constitutional provisions for partial self-government. It provided for a legislative assembly with 25 seats for elected members out of 32. The electoral base was expanded, with the majority party forming the government.

In line with the gradual political liberalization, the university authorities had permitted the registration of the Socialist Club in 1953, a standard feature in the elite British universities. However, the limits of what activities would be permissible for the Club was a matter of judgment. Governor John Nicoll (1952-55) a career colonial official for 31 years deemed that the Club was disruptive and potentially threatening. Malcolm MacDonald, governor general (1946-48) and British commissioner general (1948-55) in Southeast Asia, a reformist Labour party politician who took credit for the creation of the University of Malaya in 1949 and was its first chancellor was more liberal. Nicoll decided to charge the Fajar editorial board for sedition; MacDonald had preferred to have the vice-chancellor warn the students about getting into trouble.

In the end, MacDonald’s view that an open trial with Pritt defending was likely to work against the state prevailed. Immediately after our acquittal without defence being called, I received a phone call from his office with an invitation for dinner. No doubt, photos of the two of us enjoying each other’s company would be splashed in the newspapers, wiping out the anti-colonial effects of the Fajar trial. I did not oblige him.

On the same day of our arrests on 28 May, the director of education summoned the school management committees and principals of the key Chinese middle schools and demanded greater control over the students, the enforcement of greater disciplinary training, the re-registration of all students, and the expulsion from school of students of call up age who had not registered for national service.

The students of the University of Malaya and the Chinese high schools, the highest level education institution for the two language streams, had found one another thanks to the persecution by the colonial authorities. We were a new energetic political force of younger generation on the left. In the 1955 elections less than a year later, the pro-colonial party was decimated.

Fajar: The Hock Lee riots

In his 2008 tribute to commemorate the passing of M K Rajakumar, my closest friend and comrade and the key person behind ‘Aggression in Asia’, Tan Jing Quee observed that the 1954 trial had “catapulted” Fajar into “a major left-wing journal in the country”. Fajar kept abreast with socialism and developments in the socialist world, published essays on race and political economy in Malaya, and scrutinized ongoing political moves and events in Singapore. Today, this “major left-wing journal in the country” has become a valuable documentary source on the debates and issues in Singapore’s history that have been silenced until the last one and a half decades. The history of the 1950s and early 1960s imposed by the ruling party to this day has been no more than the relentless labeling of its opponents as communists.

Fajar’s tracking of the Hock Lee riots as events unfolded demonstrates the Club’s engagement as a grounded, critical voice alert to the wiles and lack of scruples on the part of the colonial power and its local collaborators. Its analysis of the May 12 1955 Hock Lee riots is one of its most incisive on the 1950s. (See ‘Crisis in the Left’, Fajar, no. 19, May 31 1955). As the country’s first chief minister, David Marshall had moved the motion in the first Legislative Assembly sitting on 22 April 1955 that in three months’ time, his government would decide whether the main provision in the Emergency Regulations which provided for detention without trial was necessary. Fajar discerned from this that “the riot was used as a propaganda weapon to prevent the Government from carrying out the promised reform of the Emergency Regulations”.

Indeed, with the Hock Lee riots, the government passed the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance (PPSO) in October 1955 which retained detention without trial. On top of that, the Ordinance would be in force for three years, instead of three months under the Emergency Regulations.

Fajar’s analysis is highly pertinent. It would not make sense for “communist instigators” to derail Marshall’s declared aim of reviewing the Emergency Regulations by fomenting chaos and violence at this time. It was the colonial power and its collaborators who benefitted from the riots.

Fajar: ‘Merger and Malaysia’

Tan Jing Quee’s essay ‘Merger and Malaysia’ in Fajar December 1961 (Vol lll no. 8) makes sense of Federation of Malaya prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman’s surprise declaration of support on 16 October 1961 for Singapore to be included in a merger with Malaya, and the Borneo states and explores why the Singapore government would agree to the terms of merger which were clearly unfavourable for Singapore.

The so-called “Battle for Merger” is the most cynical and diabolical manipulation of politics and massive wielding of the PPSO on trumped up charges that Singapore has witnessed. Debates in the Legislative Assembly were unabashed displays of Cold War rhetoric against the left, the obfuscation of facts on crucial issues such as nationality and citizenship, and the hollowness of Singapore’s autonomy over labour and education given that they were subject to the overall supervision of internal security by the Federal government. Tan observed that the “freak arrangement” that was merger was to bail out the PAP government. The political fortune of the PAP had been hinged on anti-colonialism, but once in power, the party abandoned its mass base, relying instead on British patronage and alliance with the right wing government of Malaya to destroy its erstwhile powerful left wing forces.

This came to pass with Operation Coldstore. Along with the mass arrests, was the ban on Fajar.

‘Merger and Malaya’ reached the heart of the merger issue which the left, led by the Barisan Sosialis of which I was the deputy to secretary general Lim Chin Siong warned against. We were bombarded relentlessly with accusations of being communists, sham debates in the Legislative Assembly, a blatantly biased media including the sensational ‘Radio Talks’ series, fear-mongering, and the most unscrupulous ‘referendum’ that could be conceived. The wonder of it is that till today, the PAP takes great pride in its chicaneries and deceit despite the failure of merger within two years.

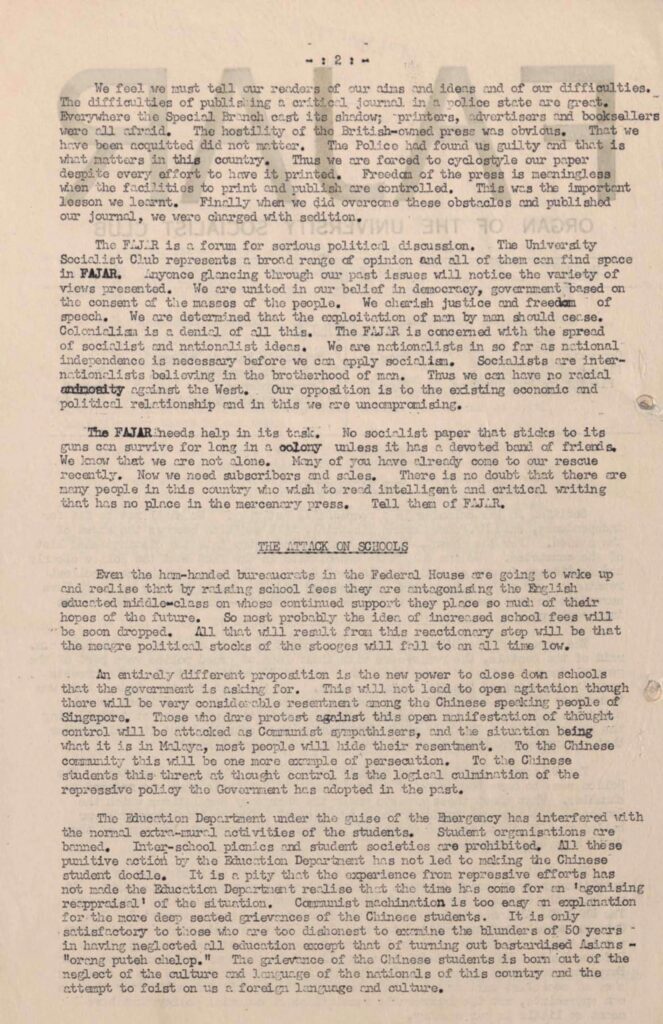

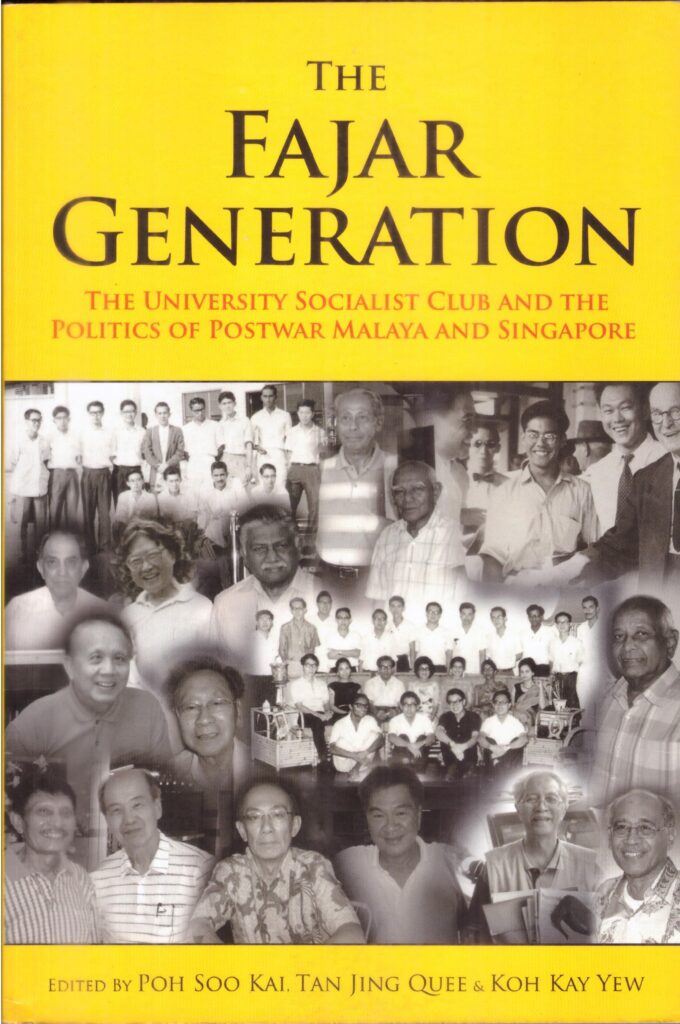

The Fajar Generation

The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of postwar Malaya and Singapore, published in 2009 brought Fajar back into public consciousness. I was the editor, along with Tan Jing Quee and Koh Kay Yew. We served as the Club’s president in 1954/1955, 1961/62, and 1965 respectively.

If not for Tan Jing Quee, we would not have this book today.

I had spent much of the long years in prison reflecting on how my comrades and I constituted threats to the dominant ruling party, and the prevailing international world order. On my release, I realised that there were no avenues to fight for accountability for the injustice done to us. We had to take a long term view. I headed to the UK National Archives in 1993, when the documents of the period up to 1963 entered the public domain with the expiry of the period of embargo. I read every file from 1956 and shared my photocopies and notes with Tan Jing Quee, Koh Kay Yew, M Rajakumar and Lim Hock Siew. We had extensive discussions, but did not go beyond that.

A breakthrough came when Michael Fernandez and Tan Jing Quee presented a talk at February 2006 fringe arts festival event with the theme Detention-Writing-Healing. The audience of largely young people had no inkling of what political imprisonment in Singapore was about. Jing Quee explained that political prisoners in Singapore were worse off than convicted criminals for they were not allowed to defend themselves in a court of law, and their imprisonment could be renewed every two years without limit.

The minister of home affairs responded with a warning: “ex-political detainees will not be permitted to rewrite history”.

Following the talk, Jing Quee started planning on a book on the University Socialist Club. He visited me a good number of times to urge me to participate. Each time, I did not give him a commitment. I did not say so, but I was afraid of being re-arrested.

On the last occasion, he was upset, and abruptly walked out of my house.

Jing Quee’s wife, Rose, came back in and said, “Soo Kai, please write”.

I agreed to do so, realizing just how much the project meant to him.

The launch of the book on 14 November 2009 was carefully planned. We decided that it would be held in Singapore and the venue was made known only at the last minute. My speech was a rambling one, full of innuendoes which the audience had trouble following.

But a barrier had been broken. As Jing Quee said to me, “No one would have believed that a medical doctor and a blind man could publish this book”.

At the book launch in Penang two months later, I found myself declaring spontaneously in response to a question from the audience: “We are not re-writing history. We are writing history”.

We have not looked back since.

The Fajar Generation

At 92, I am the oldest surviving member of the Fajar generation who are Singaporeans, with the exception of Michael Fernandez who is a year older, but there are a number of seniors who are Malaysians. At this age, one’s circle of friends gets smaller by the day. Just this week, I was informed that Socialist Club member Agoes Salim had passed away in Kuala Lumpur (15 March 2024). Agoes had contributed a brief sketch of his Socialist Club activities in The Fajar Generation. He recalled that he went around the student hostels collecting money for the bus workers in a big tussle with the employers, and helped the PAP campaign in the 1955 general election. He was president of the USC in 1956. An economist, he served in senior positions in the Malaysian government. We met from time to time in KL. He was always comradely.

The attrition of time will continue to take my USC comrades away. The youngest would now be around 80 years old. Among them, is fellow editor Koh Kay Yew who phones regularly, and visits when he is in Malaysia. With him, I can discuss theoretical issues on socialism and critiques of the neo-liberal economy. We go back such a long way.

I have also renewed friendships with so many people since The Fajar Generation. Tan Kok Chiang and his brother Kok Fang, friends since the May 13 days when they were in the Chinese middle school anticolonial movement were editors respectively of The May 13 Generation: The Chinese Middle Schools Student Movement and Singapore politics in the 1950s (2011), and The 1963 Operation Coldstore in Singapore: Commemorating 50 years (2013). Both titles were the initiative of Tan Jing Quee, and are sequels, so to speak, of The Fajar Generation. Kok Fang has made countless speeches at public gatherings when he was invited to speak. They have also translated our writings and speeches, being effectively bilingual.

There are also Barisan, labour union and other former political prisoners, some of whom were a little younger and mainly Chinese-speaking—part of the “Old left”. We have renewed our friendships, and they have introduced me to new friends, some of whom have visited a good number of times, one group packed in a mini bus. They discuss how to keep our socialist ideas and spirit alive in Singapore today.

Having our history in writing has made us proud of our past and helped rebuild solidarity after decades of silence and isolation. We have consolidated ourselves into a Generation, so apt a term that Jing Quee employed.

Fajar Generation+

More importantly, the Fajar generation is not limited only to those who were in the forefront of political activism in the 1950s and early 1960s and imprisoned under the Internal Security Act. I regard as Fajar generation+ those younger people that I have come to know through the decades, who in their own ways have a principled stand and taken action against injustices and exploitation, pitting themselves against the powerful status quo. I am convinced that no matter how bleak, there has been and will continue to be, Singaporeans who will stand up for secular human values, justice and peace and who value our history and shared vision.

今年( 2024 年),是《华惹》(Fajar)第 7 期(1954 年 5 月 10 日出版)社论《对亚洲的侵略》(Aggression in Asia)发表 70 周年,该社论导致《华惹》编辑委员会一众成员于当年 5 月28 日因煽动叛乱罪被捕,随后被起诉。 身为大学社会主义俱乐部主席、俱乐部会刊《华惹》出版人,我是八名被告之一,是当中的领头羊。 我当时22岁,大学医学院三年级学生。 九年后,我31 岁,在“冷藏行动”(Operation Coldstore)中被未经审判拘捕下狱。经过1973年12月至1976年6月期间(在强加限制令下获释)的短暂自由后,我在1976年重新被捕,直至年届50岁才被释放。我77岁时,《华惹世代:大学社会主义俱乐部以及战后马新政治》(The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore)一书出版,我是该书编辑之一。

如今我已达92岁高龄,庆幸自己仍有机会纪念华惹诉讼案。新加坡去殖民化进程中,这是一个里程碑。

华惹诉讼

华惹诉讼案改变了我,想必也改变了我那些共同被告友人们的一生。 该事件也改变了英国殖民统治者为新加坡所制定的战后政治进程。

我们并未预料到会因为发表《对亚洲的侵略》一文而被捕,并成为头条新闻。事实上,我们在谴责东南亚条约组织(SEATO)的成立时,小心翼翼地引用了英国左翼工党著名领导人的相关言论,认为这是促使地缘军事化的步骤,从法国正在进行镇压越南反帝国主义运动的战争中体现出来。 我们争辩指出,马来亚正在变成殖民战争的军事基地,我们的青年被征召入伍参战。

我们也无法预知,5月13日,《对亚洲的侵略》发表三天后,华校中学生会因为反对在籍学生完成兵役登记而遭到警方袭击。 我们和中学生们站在一起。 在我们被捕前一天,大学学生会开会,讨论谴责警方暴力对待中学生的议决案。(参见《华惹》第 11 期,1954 年 9 月 20 日出版)。

因为华惹诉讼案和 513 警察暴力事件,“孟迪卡”(Merdeka,独立),从此成为新加坡政坛近十年里最流行、最具影响力的口号。

以煽动叛乱罪(即煽动人民反抗皇室权威)逮捕起诉大学社会主义俱乐部成员引起轰动。而此案在法庭遭法官驳回,引起更大的轰动。

帮我们辩护的丹尼斯·普里特( D N Pritt)女皇律师,曾是各地反殖领袖,包括印度革命者、肯尼亚独立战士和胡志明的代表律师。约翰·埃伯(John Eber),资深律师,已解散马来亚民主同盟 (Malayan Democratic Union, MDU) 主要领导人,1951 年在紧急法规(Emergency Regulations)下被不经审判拘押,1953年获释后移居英国。他为我们物色并联系了两位著名律师。 我选了普里特。普里特让我们研究各英殖民地发生的煽动叛乱案件,从阿姆利则(印度)到峇冬加里(马来亚)。 他打算把法庭上的诉讼变成一起政治事件。

紧急状态与华惹诉讼案

我认为马来亚民主同盟的左派,是我们反殖民运动的先驱。 民盟在第二次世界大战日本战败后成立,由新加坡受英文教育,反对英国回来重新殖民的马来亚人组成。 民盟吸引了年轻律师、莱佛士书院毕业生、文员以及战后合法化的马来亚共产党党员加入。

民盟时期的政治活跃空间没能维持太久。1948年6月殖民当局宣布紧急状态。马共再次被列为非法,在马来半岛对英殖民军队发动森林游击战。 1949年10月,中国共产党领导的中华人民共和国成立。新加坡岛上的政治镇压接踵发生。 1950 年 5 月,英国人成功捣毁了他们声称负责指挥马共活动的星洲市委。 警方突袭搜查华侨中学和南洋女中,两校停课两个月,约二十名学生在紧急法规下被捕。 1951年,约翰·埃伯等民盟左翼成员和马来亚大学学生被捕。 随着出台系列镇压反殖团体的闪电战,殖民当局做好了扶植门徒,安置在受控的去殖民化运动中担任政治领导角色的准备。

1953年林德委员会成立,负责制定与组建部分自治政府相关的宪法条款。根据林德宪制,在立法议会32 个席位中,民选议席占 25 个,借此扩大民选基础,并规定由赢得多数议席的政党组织政府。

和政治的逐步开放相一致,1953年大学当局允许社会主义俱乐部注册,这是英国精英大学的标准特征。 然而,对社会主义俱乐部可从事活动应施加何等限制,则是个决策问题。约翰·尼诰(John Nicoll)总督(1952-55 年),一个31年资历的职业殖民地官僚,认为社会主义俱乐部具有破坏性和潜在威胁。 马尔科姆·麦克唐纳(Malcolm MacDonald)总督(1946-48 年),英国驻东南亚专员总长(1948-55 年),则是一位改革派工党政治家,他因 1949 年创建马来亚大学而广受赞誉,为该大学第一任校长,此人立场相对自由开明。 尼诰决定以煽动叛乱罪起诉华惹编委会;麦克唐纳更希望可由大学校长出面,劝诫学生克制不要惹麻烦。

麦克唐纳担心,由普里特担任辩护律师的公开诉讼过程,可能出现对国家不利的状况。最终,麦克唐纳的观点占了上风。在我们还未被传召辩护就宣判无罪后,我几乎即刻接到了他办公室邀我去吃晚餐的来电。 我们两人惬意一起进餐的照片若出现报端,华惹诉讼案引发的反殖情绪,无疑将很大程度被抵消掉。 我没答应赴约。

5月28日,我们被捕的同一天,教育局局长召集了学校管理委员会和华文重点中学的校长,要求加强对学生的控制,如强化纪律训练,对所有学生实行重新注册,以及将未完成兵役登记的适龄学生开除出校。

马来亚大学和华侨中学,来自两所不同语文源流最高学府的学生,竟由于殖民当局的迫害而找到了彼此。 我们年轻一代由是形成了一股充满活力的新的左翼政治力量。 在不到一年后的 1955 年大选,亲殖民地的政党惨遭碾压。

华惹怎么说:福利巴士工潮

陈仁贵(Tan Jing Quee),我最亲密的朋友与同志,《对亚洲的侵略》一文背后的关键人物,2008年悼念拉惹古玛 (M K Rajakumar)时指出,1954 年诉讼案使《华惹》瞬间成为“当地主要的左翼刊物”。《华惹》紧跟社会主义和社会主义世界的发展局势,发表马来亚种族和政治经济相关的分析文章,密切关注新加坡的政治动向与事态。 今天,这个“当地主要的左翼刊物”成了辩论与了解新加坡历史的宝贵文献来源,重新激活了过去十几二十年来一度沉默的状态。 执政党如今讲述的五六十年代历史,除了给对手无情贴共产党标签外,什么都不是。

《华惹》对福利巴士工潮的追踪报道,反映了大学社会主义俱乐部介入,发出的是接地气而直中要害的声音,有别于殖民当局及其同伙的鬼话与恬不知耻的胡言。 《华惹》对 1955 年 5 月 12日福利巴士工潮的分析,是该刊50 年代最具深度的文章之一(见《左翼的危机》,《华惹》第19 期,1955 年 5 月 31 日出版)。马绍尔(David Marshall),新加坡第一任首席部长,1955 年4 月 22 日在第一届立法议会提出动议,承诺他治下的政府将在三个月内决定,紧急法规(Emergency Regulations)中关于不经审判拘押的条款是否有必要保留。《华惹》从中看出,“福利巴士工潮演变成骚乱,其实是某种宣传武器,旨在阻止政府落实改革紧急法规的承诺”。

事实上,利用福利巴士工潮演变成骚乱,1955 年 10 月政府通过了“维护公共安全法规”(Public Security Ordinance, PPSO),保留了不经审判拘押的条款。 不单如此,该法规下不经审判拘押的有效期为三年,而不是紧急法规中的三个月。

《华惹》的分析鞭辟入里。 “共产党煽动者”发起暴动、制造混乱,来破坏马绍尔审查改革紧急法规的承诺,这简直狗屁不通。骚乱的受益方,恰恰是殖民当局及其合伙人。

华惹怎么说:合并与马来西亚

陈仁贵 1961 年 12 月在《华惹》(第 3 卷第 8 期)发表文章《合并与马来西亚》,解释马来亚联合邦总理东姑阿都拉曼 1961 年 10 月 16 日出人意料宣布支持新加坡、婆罗洲与马来亚合并的声明, 并对新加坡政府为什么会同意显然对新加坡不利的合并条款进行了探讨。

所谓“争取合并的斗争”,是迄今为止新加坡所目睹最讽刺、最邪恶的政治操纵,也是迄今为止新加坡所见证挥舞着维护公共安全的大棒子,肆无忌惮捏造罪名的大规模运作。立法议会的辩论,尽是些赤裸裸针对左派的冷战话术,在国籍和公民身份等关键问题上只能混淆事实颠倒是非,至于新加坡在劳工与教育政策上享有自治权,因为受联邦政府基于国家内部安全而实施的全面掌控,这类自治并无任何实质意义。陈仁贵还观察到,合并这一“奇葩安排”无非为了拯救人民行动党政府。人民行动党的政治前途和反对殖民主义休戚相关,但该党在掌权后就背弃了其群众,转而依靠英国的庇护,与马来亚右翼政府结盟,意图摧毁其昔日坚强盟友的左翼势力。

冷藏行动实现并凸显了该意图。在推进大规模逮捕的同时,《华惹》被查禁了。

“合并与马来亚”才是合并问题的核心,以社会主义阵线为首的左翼对此提出了警告。林清祥是社阵秘书长,我是他的副手。 我们受到了铺天盖地的无情抨击,胡乱指控我们是共产党,立法议会里尽是言不及义的虚假辩论,摆明偏袒的媒体(包括耸人听闻的“广播谈话”系列),散布兜售恐慌情绪,以及不择手段之最的“全民投票”。 奇妙的是,尽管合并在两年内即宣告失败,人民行动党至今仍对其诡计和欺骗行径感到自豪。

《华惹世代》

《华惹世代:大学社会主义俱乐部以及战后马新政治》一书,2009年出版面世,把《华惹》重新带回到公众视野当中。我是该书编辑,其他编辑有陈仁贵和许庚猷。 我们是社会主义俱乐部的先后主席(傅树介,1954/1955年;陈仁贵,1961/62年;许庚猷,1965年)。

要不是陈仁贵,我们今天不会有这本书。

我在漫长的牢狱岁月里,针对我和我的战友们究竟是如何对占据主导地位的执政党,以及现行的国际社会秩序构成威胁的,花了许多时间思考。 获释后,我意识到没有任何途径可以为我们所遭受到的不公待遇追究责任。 风物长宜放眼量。我们只好采取长远的目光。 1993 年,英国前于并截至1963年的档案,保密期限届满解禁,我于是动身前往英国国家档案馆。 我读了 1956 年以降的所有文件,并与陈仁贵、许庚猷、拉惹古玛和林福寿分享了我的复印件和笔记。 我们进行了广泛的讨论,但也仅限于此。

直至2006 年 2 月,迈克·费南德斯(Michael Fernandez )和陈仁贵在艺术节“艺穗”活动上发表题为“拘留-写作-治疗”的演讲,这才打破了僵局。 当时的观众主要是年轻人,对新加坡的政治监禁一无所知。陈仁贵解释说,新加坡政治犯比定罪的罪犯处境更糟,因为他们不被允许在法庭上为自己辩护,而且他们的监禁可以无限期地每两年延续一次。

内政部长以警告对此作出回应:“我们不会允许前政治犯改写历史”。

演讲结束后,陈仁贵开始计划要写一本关于大学社会主义俱乐部的书。他多次拜访我,敦促我参加。 每一次,我都不给他许诺。 我没说出口,其实我害怕重新被捕。

最后一次,他很不高兴,骤然疾步从我家走了出去。

仁贵的妻子 Rose 返回来说:“树介,你写吧。”

这回我答应了。因为意识到这项工作在仁贵心目中的意义。

该书在 2009 年 11 月 14 日发布,这是细心策划的。 我们决定在新加坡举行发布会,但要等到最后一刻才公布地点。 我的演讲乱无章法,充满影射,让听众听得一个头两个大。

但不管怎么说,魔障总算是破除了。 正如仁贵对我说的那样,“没人会相信,一个医生和一个瞎子,竟可以捣弄出版这么一本书”。

两个月后,在槟城的新书发布会上,我发现自己在回答观众提问时自发宣称:“我们不是在改写历史。 我们正在书写历史。”

从那时起,我们再也没有回头。

华惹世代

我今年92岁,是仍在世的华惹世代中年龄最长的新加坡人,迈克·费南德斯除外,他比我大一岁;另外还有不少比我年长的,但都是马来西亚人。 到了这般年纪,朋友圈一天天见缩小。 就在本周,我获悉社会主义俱乐部成员阿戈斯·萨利姆(Agoes Salim)在吉隆坡去世了(2024年3月15日)。 阿戈斯在《华惹世代》书中概要介绍了他自己在社会主义俱乐部的活动。 他回忆说,曾经穿梭走遍学生宿舍,为与雇主激烈抗争中的巴士工人筹款,以及在1955年大选中为人民行动党助选。 他是社会主义俱乐部1956 年的主席。作为一名经济学家,他历任马来西亚政府的高职。我们有时在吉隆坡会面。 他总是表现出同志般的热情。

时间的耗损,将继续带走我社会主义俱乐部的同志们。他们中最小的,现在怕也已经80左右岁了。他们当中的许庚猷,我《华惹世代》一书的编辑伙伴,经常打电话来,到马来西亚时也会来访我。 我和他可以一起讨论社会主义的理论问题和对新自由主义经济的批判。我们毕竟相知了那么久远。

自《华惹世代》出版以来,我跟许多人重新建立了友谊。 陈国相和他的弟弟国防,是513那时的老友,他们当时参与了华校中学生的反殖民运动,分别是《情系五一三:一九五零年代新加坡华文中学学生运动与政治变革》(2011)以及《新加坡1963 年的冷藏行动. — — 50 周年纪念》(2013 年)两书的编辑。该两部书都出自陈仁贵的倡议,可说是《华惹世代》的续作。 陈国防曾多次受邀在公众集会上演讲。他们双语能力都强,很做了些我们书写与演讲的翻译。

还有社阵、工会和其他前政治犯,其中有些年龄稍小,主要讲华语,属于“老友”的部分组成。我们重新建立了友谊,他们还给我介绍了新朋友,其中有些人已多次来访,一群人挤在一辆小巴士里前来。 他们讨论如何在今天的新加坡维系我们的社会主义理念与精神。

把我们的历史写成书面,让我们为自己的过去感到自豪,并帮助我们在经过数十年的沉默与孤独后重新团结。我们已经将自己整合为一个世代,这是仁贵一个非常贴切的用词。

华惹世代+

更重要的是,华惹世代不应局限于那些五十年代及六十年代初投身政治活动前线,并在内部安全法令下被捕入狱的人。我把自己这几十年来认识的年轻人,视为华惹世代+。他们以自己的方式坚持原则与立场,采取行动反对不公与剥削,对抗强大的现状。 我深信,无论前景怎么黯淡,总会有为了世俗的价值、正义与和平挺身而出,珍视我们的历史和共同愿景的新加坡人。这样的新加坡人,曾经有,下来继续会有。

The Arrest – 21 May 1987 (Thursday)

16 people arrested at about 5am under the Internal Security Act (ISA). They were:

They were blindfolded, handcuffed and brought to Whitley Detention Centre at Onraet Road, a prison hardly known to Singaporeans. There they were registered, fingerprinted, photographed, medically checked, and given beige-coloured pyjamas to wear minus underwear and accessories including spectacles, wristwatches and footwear. Thereafter, they were brought to the basement cold-rooms or ground-floor open rooms for interrogation.

Interrogation started in the morning of the first day and continued round the clock for two to three days. When confessions were not forthcoming, harsh tactics were used. Some were made to stand up for long hours, sit unbalanced on chairs with uneven legs; others were slapped and/or beaten, yet others were doused with water while they shivered from the cold. All had to endure deprivation of proper sleep and rest for days.

Meanwhile, family members and friends of the arrested frantically looked for explanations and consolation. It was a time of confusion, disbelief, frustration, worry and grief.

First Week

The next day (22 May 1987), The Straits Times gave a brief report of the arrest. The Government said the arrests were “in connection with investigations into a clandestine communist network.”

The Church, its clergy and the lay organisations met to discuss the arrests, issuing letters and statements expressing confidence in the integrity and motivation of the church workers. Swift responses also came from foreign organisations who together with local organisations like the Law Society and the Workers’ Party called for the 16 persons to be charged or released unconditionally. Some family members of detainees held a press conference to reject the allegations and appeal for release.

Archbishop Gregory Yong met with families of detainees, expressing his concern and support for the Church workers. The Church later issued a press release on behalf of the church organisations involved: “We wish to know if these confessions have been given under any form of duress, coercion, intimidation, threat, fear or inducement.”

Meanwhile in prison, detainees were frantically interrogated to confess to a Marxist plot to overthrow the State. Vincent Cheng was forced to write and sign pages of self-incriminating “facts.” A chart portraying the Marxist network with Tan Wah Piow and Vincent Cheng at its centre was created by the ISD and, according to one detainee, shown to him on the first day of interrogation.

After six days of official silence, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) issued on 26 May 1987 a 16-page statement on the arrests.

The Second Week

After a week of total blackout of both international and local reactions to the arrests, The Straits Times (ST) acted as the official vehicle of MHA’s report of the arrests. For a whole week from 27 May 1987, the ST reported in its front pages the government’s conspiracy theory about how it had uncovered a Marxist plot masterminded by Tan Wah Piow, a political exile in Britain, and operated by Vincent Cheng and his co-conspirators in Singapore, using communist united front tactics, to subvert the Church, the Workers’ Party and the State. Many people reacted to the report with scepticism.

Foreign organisations representing the Church, journalists, lawyers, workers, artistes and NGOs dismissed the government’s allegations, stepped up their opposition to detention without trial and offered solidarity to the detainees.

Families were allowed to briefly see their loved ones in prison for the first time on 27 May. A few detainees could also see their lawyers. The ISD tried to present to the public that the detainees were well-treated and properly cared for. Some detainees were suffering health problems.

The Church continued to pour cold water on the government’s allegations. A solidarity Catholic mass was celebrated on the 27 May evening by the Archbishop and 23 priests at Our Lady of Perpetual Succour Church to pray for the detainees and their families. The church was packed to capacity of 2500 people. Internal security policemen were said to have monitored the celebration.

Next day, the Catholic archbishop and his priests met and released a statement expressing their confidence in the Church’s full-time and volunteer workers and the organisations they worked for. At the weekend, the archbishop released a Pastoral Letter read in all Catholic churches wherein he endorsed the Church’s support for the detained Church’s workers.

Tan Wah Piow, the alleged mastermind of the conspiracy, issued a long and detailed statement in reply to the government’s charges against him. The statement was banned in Singapore. The next day, Tan received in London a registered letter dated 21 May 1987 (the day of the detainees’ arrest) informing him that his citizenship was revoked.

Opposition politicians J.B. Jeyaretnam, Wong Hong Toy and Mohamed Jufrie from the Workers’ Party staged a protest in front of the Istana on 30 May, saying that the Marxist threat was a figment of the Government’s imagination. They were promptly arrested but later released.

The Church’s refusal to accept the government story was criticised by Foreign Minister S. Dhanabalan. The Pastoral Letter of the archbishop had provoked the fury of the government. Relations between the Catholic Church and the government appeared to be on a collision course. Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew stepped in and wanted a meeting with the Church. Out of a list of 19 names compiled by the Church for the meeting, 3 were axed by Catholic lay leader Mr Ee Peng Liang and 6 axed by the Internal Security Department (ISD). The remaining 9 persons (5 priests, 1 nun, 3 laypersons) were allowed to accompany the Archbishop to meet the Prime Minister at the Istana.

The Istana Meeting – 2 June 1987 (Tuesday)

The Church delegation arrived for the meeting at 2.15pm. They were first given 30 minutes to read the ISD report on Vincent Cheng and his signed hand-written “confessions.” At 3pm the delegation met the Prime Minister who then lectured the Church on the crisis. He first articulated his respect for and the government’s good relations with the Catholic Church. Maintaining that the 16 detainees were no threat at all, that Tan Wah Piow was a “simpleton” and Vincent Cheng and the others were “novices” and “do-gooders”, he indicated that he was more concerned about the Church being used by communists who under the cover of religion was destabilising the State, just like in the Philippines. The Archbishop, he said, had not heeded the warning signs given by the MHA to him earlier. In no uncertain terms he said that the government would deal with errant priests, even under the ISA. Here for the first time, the delegation learnt of the four priests identified by the ISD for immediate action. The Prime Minister also warned the Archbishop that if the Church gave cover to the 16 detainees, it would complicate matters.

In response to the lecture by the Prime Minister, the Archbishop said the he was satisfied that the government was not attacking the Church but those who use the Church to subvert the State. Regarding the depositions of Vincent Cheng, the Archbishop was heard to have said: “I will take things on their face value for now”, but these words were not reported in the press or on TV. (Far Eastern Economic Review 17/12/87)

While some members of the delegation felt that the government had a case against Cheng, others saw it as an attack on the Church. Mr Ee Peng Liang who was asked by the Prime Minister (PM) to arrange the meeting, said: “Now the matter is clear. We read the files, the PM briefed us and we are satisfied.” (ST 3/6/87; FEER 17/12/87). The nearly two-hour meeting ended at 4.45pm. But the Archbishop was not prepared for the PM’s next move.

The Archbishop was hauled back for another meeting. Unknown to him, the Secretary to Pope’s Representative based in Bangkok had been flown down and had a meeting with the PM earlier at the Istana. The PM wanted two things: firstly, the Archbishop to come out with a decisive statement without implicating him (PM), and secondly, both the Archbishop and the Secretary to appear before a press conference with the statement. In the circumstances, Archbishop Gregory Yong and Rev. Giovanni D’Aniello said: “We are satisfied that the Government of Singapore has nothing against the Catholic Church when it detained ten of our Church workers amongst the 16 who were arrested for possible involvement in the clandestine Communist network.” (ST 3/6/87).

The Archbishop left for home to meet his awaiting priests, and one of them clearly heard him utter “I was cornered”. (This utterance would become an issue at the PM’s defamation suit against the Far Eastern Economic Review in January 1989).

At the same press conference, the PM said the detainees would not be put on trial: “It is not a practice nor will I allow subversives to get away by insisting that I got to prove everything against them in a court of law or evidence that will stand up to the strict rules of evidence of a court of law…..So long as we know it is true, so long as there has been no torture, no coercion, no distortion of the truth, that we are satisfied, we are prepared to act. But we will not act on concocted evidence.” (ST 3/6/87)

A delegation of family members of the church detainees met with the Archbishop at 8pm to look for his support in these trying times. By now, after the experience earlier at the Istana, the Archbishop was starting to waver. He wanted to disengage the Church from supporting the detainees and to be non-committal. The family members felt betrayed and reacted with disgust and bitterness.

Then at 9pm, the television news broadcasted that, on the basis of the documentary evidence presented to him which he had no way of disproving, the Archbishop accepted the Government’s allegation that Vincent Cheng was a key figure in a Marxist plot to subvert the state. The next day’s (3 June) Straits Times splashed its front page headline with: “Archbishop accepts evidence.” For several days thereafter, extensive pages were devoted to show how Cheng used the Church as a cover for his subversive activities, and how there was no conflict between the Catholic Church and the government.

The Third Week

From then on things happened in quick succession. The attacks of the government were now aimed at the four priests who from the beginning of the arrests had regrouped into a committee of co-ordination: Fr. Joseph Ho (chairman of the Justice and Peace Commission), Fr. Edgar D’Souza (assistant editor of The Catholic News), Fr. Patrick Goh (national chaplain of the Young Christian Workers), and Fr. Guillaume Arotcarena (director of the Catholic Centre for Foreign Workers). After being briefed by the delegation on the Istana meeting, the priests realised that the PM’s will was not so much the prolongation of the detention of the 16 as the elimination of the four priests. To diffuse the situation, the four priests decided to tender their resignation from the organisations they served. The Archbishop accepted the resignations and gave a press conference about it, expressing his hope that the affair was now nearing its conclusion. He also banned the forthcoming issue of the Catholic News which highlighted the arrested church workers. The Archbishop’s hope was dashed when word came from the Church’s Vicar General that the ISD wanted more than resignation. They wanted ecclesiastical sanctions on the four priests, and the Archbishop gave in by “suspending the four priests from preaching and from having anything to do with the organisations they were once in charge of.” (ST 6/6/87). One by one, the four priests left the country.

Heeding the government’s warnings and trying to make good his pledge at the Istana meeting to put his house in order, Archbishop Yong began the big turnaround. The Justice and Peace Commission was shelved, the Catholic Centre for Foreign Workers was closed down, the Catholic social movements were to be monitored more closely, the Catholic News would return to a more “religious” spirit, priests and religious were instructed to keep religion and politics apart especially in their sermons, and intercessory prayers for the detainees prohibited in worship sessions.

On 6 June, 16 family members and friends of detainees wrote to Pope John Paul II describing how the local Church’s initial support evaporated overnight, how the Archbishop did not questioned the means by which signed depositions were obtained, and how he prohibited intercessory prayers for detainees in masses.

Despite the subservience of the local church, fellow Catholic churches around the world were not so accommodating. The Australian Catholic Church had made its support of the 16 by political action and prayer sessions. Archbishop Soter Fernandez and Bishop Selvanayagam of Malaysia called on the government to try the 16, saying: “In view of the recent press release from Singapore concerning the deposition of Vincent Cheng, we insist all the more that the evidence be brought to an open court.” 120 national Catholic organisations meeting in Rome sent a telegram to the PM requesting immediate release of the 16 pending due process of law and justice.

J.B. Jeyaretnam, Secretary-general of the Workers’ Party held a press conference, demanding that the government release the detainees. He said that the fact that the government would not take them to court proved there was no evidence against them.

Local scepticism of the government’s story continued despite its detailed Report carried in The Straits Times and other local media. The government embarked on its next step – television confessions. Vincent Cheng was the first to be pressured to do so. His confession, rehearsed and pre-recorded, was aired on 9 June on prime-time television (78 minutes).

International Reactions

Now that the government had achieved the goal of getting the Church to toe the line, it had to fight another battle. The international response to the detentions was antagonistic and persistent. Many organisations and concerned individuals wrote to the government or the families of the detainees, demanding genuine legal redress and immediate release. The government found it difficult to overcome or tame them. The international organisations wanted precise answers to their inquiries. Some went further to carry out protest demonstrations at Singapore embassies or corporations such as Singapore Airlines.

The foreign media was undaunted. Major publications such as Far Eastern Economic Review, Asiaweek, Asian Wall Street Journal, The Age, and The Star raised more questions than answers regarding the alleged Marxist Conspiracy.

In Malaysia, Singapore’s closest neighbour, many sessions were organised to inquire into the truth of the government’s allegations and to offer solidarity. Besides the Church, other secular groups also made statements. One group comprising 14 organisations and calling itself “Human Rights Support Group for the Singapore 16” called on the Singapore government to release the detainees or bring them to court. The same call was made by “The Penang Support Group for the Singapore Detainees.”

The Malayan Trade Union Congress Youth Section wrote to the Singapore government: “We are against the concept of detention without trial. All are innocent till proven guilty.”

A research group called Institute of Social Analysis (Malaysia) organised a forum on 10 June, with speakers from Aliran, Malayan Bar Council, and Malaysian Social Science Association. The forum declared its opposition to confessions obtained under torture and duress, and thus refused to accept such confessions of the 16 detainees.

Amnesty International began their inquiry. A delegation went to Singapore to investigate and work on the case from 14-21 June 1987. On their return, on 26 June, Amnesty adopted 12 of the detainees as prisoners of conscience. It also produced a document on the case, arguing against the use of harsh treatment and coercion in continuous interrogation.

Three organisations: International Commission of Jurists (Geneva), International Federation of Human Rights (Paris) and Asian Commission of Human Rights (Hong Kong) formed a delegation called International Mission of Jurists to Singapore and came to inspect the case from 5-7 July 1987. They published a file on the affair, registering the reactions of more than 200 organisations including Asia Watch (USA), Korean Human Rights Committee, Justice and Peace Commissions of different countries, etc. They made a detailed study of Vincent Cheng’s TV confession and noted that at no time in the interview did Cheng admit his participation in a Marxist plot or an eventual recourse to violence.

47 law academics in New Zealand issued an open letter condemning the action of the Singapore government. In Japan, the Kansai Emergency Committee on Human Rights in Singapore, comprising church and community leaders, lawyers and academics said that the Singapore government’s charges were “ridiculous and cynical slanders.”

Political groups of the highest order also intervened. 10 members of the US Congress wrote to Minister of Home Affairs on 15 June, challenging the illegal use of coerced confessions and calling for legal procedures to begin. On 4 July, another 55 US Congressmen, including several presidents of commissions, said the same in a letter. At a meeting on 19 June, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia despatched a letter to their Singapore counterpart, demanding for an explanation of the affair. 15 deputies of the Japanese Diet also signed a letter to PM Lee Kuan Yew. The European Parliament passed a resolution on 17 June, calling on the Singapore government to review the cases of the 16 immediately.

On 17 June, Tan Wah Piow launched his book Let The People Judge: Confessions of the Most Wanted Person in Singapore in London. In a press release, he said that “the government has fabricated the communist conspiracy…for partisan ends.” He is ready to “be publicly interrogated by its officials in a neutral place, in the presence of independent observers from the media, church, law society and academic institutions.”

The First Releases and New Arrests

On 19 June, the government issued its first order on the detainees following a month of interrogation. Vincent Cheng was served a detention order for two years, and 11 others for one year. Four (Ng Bee Leng, Mah Lee Lin, Tang Lay Lee, Jenny Chin) were released the next day (20 June). Except for Jenny who was released without conditions, the other three had restrictions on leaving the country, on taking part in any activities or be members of any groups which could be used for Marxist or communist propaganda.

The next day, 20 June, the government arrested six more people. They were:

The arrests of three persons associated with the Singapore Polytechnic Students’ Union (SPSU) were deemed necessary following the actions taken by its leadership. On 6 June, acting president Fan Wan Peng, in a letter to Minister Jayakumar, denied that SPSU was ever infiltrated by Marxist elements and called for the 16 to be released or charged in court.

Following the arrests of SPSU’s president and secretary-general, members resigned in fear and the new leadership agreed to toe the government’s line. SPSU was the last vocal students’ union to be repressed.

The Sixth Week

International reactions to the arrest of the 22 remained defiant and unconvinced about the government’s explanations. Doubts were also being raised among Singaporeans.

On 24 June, former President of Singapore, Devan Nair delivered a scathing attack on Lee Kuan Yew and his government in an address to graduates of the National University of Singapore. He said the government, led by Lee, had today adopted an elitist political style that belittled the ordinary man and aimed to stifle open debate in public life. “If people do not appear willing to respond (to open debate on issues), it is because the government is known to react like a scalded polecat to even mild criticism”. In attempting to “maximise popular support through monopoly over the formation of public opinion”, the government was creating disquiet and disenchantment. (ST 26/6/87)

Minister of Foreign Affairs, S. Rajaratnam gave a dire warning on 26 June about the worldwide “hybrid beast” of communism, racialism and religious fanaticism that had now attacked Singapore. He explained how liberation theology was communism in clerical clothes, infecting countries such as the Philippines.

Because Cheng’s televised confession was not wholeheartedly received by the public, the government wanted a more sophisticated programme to be produced. Presented like a documentary, “Tracing the Conspiracy” was shown in two parts on 28 and 29 June 1987. It tried to bring together all the confessions of the detainees into a unified story as one of a long history of communist struggles with the PAP government. The central figure was Tan Wah Piow and around him were the various organisations and individuals who were preparing the ground for his return to Singapore to create a Marxist state.

July 1987

After six weeks, the government was still unable to stop and silence the questions arising from the detentions. The thorn in its side was the USA. On 2 July, two prominent government figures, namely Tommy Koh and S. Jayakumar had to reply to questions filed two weeks earlier on 15 June in an attempt to conclude foreign investigations into the detentions.

Singapore’s Ambassador to the USA, Mr Tommy Koh rebutted a Washington Post report on 15 June which accused PM Lee Kuan Yew of “intolerance of almost any form of dissent against his rule.” He said the report contained errors and omissions, arguing that Vincent Cheng had already confessed to the allegations, there was no evidence of torture or ill-treatment, the Catholic Church had accepted the government’s story, the ISD had uncovered Tan Wah Piow as the mastermind, and the Singapore Constitution expressly provided for preventive detention. To opponents who have campaigned against the ISA in general elections, he said: “Each time the electorate has given the government their overwhelming mandate.” (ST 2/7/87)

The Home Affairs Minister, S. Jayakumar wrote in reply to a group of 10 US Congressmen who questioned the legality of the public confessions of the detainees deprived of a trial. His arguments echoed much of what Tommy Koh said, relating how the British introduced detention without trial and how preventive detention had ensured economic prosperity and political freedom to Singapore. He ended by claiming that Singapore was a sovereign nation with its own rules of governance and would not bow to American values and experience.

On 5 July, in a speech at his People’s Action Party (PAP) Youth Wing seminar, Jayakumar revealed that Wah Piow was not the mastermind of the Marxist conspiracy, that he was being manipulated by others more sinister and cunning, that he was but “a puppet in a deadly game.” He said the government was now encountering a new tactic of the communists. “This time, they did not want it to be seen as a clash between government and communists, but as a clash between Church and State.” (ST 6/7/87). Regarding foreign reports of torture on detainees, he said: “We don’t do these illegal acts and expect to get away with it. Just can’t be done. And we don’t do it…. It’s really not necessary to resort to these illegal and arbitrary acts of torture.” (ST 8/7/87)

This first modification of the identity of the mastermind showed cracks in the government theory. Jayakumar had to confess that many questions were still left unanswered. The conviction expressed in his first press communiqué in May was now in tatters. To stem the tide of doubt, the government embarked on another television confession exercise on 19 July, this time making use of Chew Kheng Chuan, Tang Fong Har and Chng Suan Tze to confess to activities that support the communist cause. The three had been served with detention order for one year while the three student leaders were released on 18 July with restrictions. The focus now was to emphasise the threat of communism in Singapore, and the Minister to propagate it was none other than BG Lee Hsien Loong (PM Lee’s son and rising star of the younger leadership).

Using the television as his medium of instruction on 20 July, BG Lee said in a dialogue with community leaders, that the arrests were not an attempt to suppress the opposition or to strike “white terror” among the people. “The government’s position is clear. Anyone, who is unhappy with government policies or believes he has a better policy, can form his own political party and oppose the government openly.” But the government would not condone clandestine activities under the cover of religion to promote the communist cause. He maintained that “the communist threat is still present though it has changed its form. It has not been eradicated and will not be eradicated…. The threat is not just from the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) now…The sources of influence are the euro-communists, the extreme leftist Trotskyists…. There is also the influence from the Philippines. Though it is a Catholic nation, the Church is infiltrated by leftist elements.” The communist goal of a classless society was an “illusion.” There was a need to prevent young idealistic Singaporeans from being influenced but overseas-educated Singaporeans posed a problem. BG Lee gave three reasons why the ISA was needed to fight the communists: the clandestine nature of communist activities made it difficult to obtain evidence in a normal court procedure; witnesses faced threat of assassination; open trial would allow more publicity to extremists. (ST 20/7/87)

110 concerned Christians signed a letter dated 23/7/87 addressed to Archbishop Gregory Yong and copied to the priests and religious of the Singapore Catholic Church. They criticised the bishop and his priests for failing “to stand by those who are being persecuted for showing concern for the poor and marginalised …Your actions have robbed the Church of credibility in the eyes of everyone.” They reminded the bishop: “As leader of the Church, we would expect you to first verify for yourself the veracity of the actions of those detained before accepting the Prime Minister’s allegations…. You have placed yourself on the side of the accusers…. How can the Church preach justice when you have cooperated in the violation of a basic human right?…. You seem to have been more concerned in preserving the structure of the Church than the people who were prophetic enough to interpret the Gospels in concrete action…. You compromised Jesus Christ’s solidarity with the poor and the oppressed. You compromised the Kingdom values of Justice, Peace, Fellowship and Love”. They concluded by telling the Bishop: “However, it is not too late because the issue remains unresolved. You can still demand a fair trial in open court for all those detained and uphold their innocence unless and until they are proven guilty.”

From the beginning it was PM Lee Kuan Yew and his Minister of Home Affairs who were prominently in the forefront to expose the Marxist conspiracy. The younger leaders in the Cabinet deferred, in silence. In Parliament on 29 July, Goh Chok Tong, the First Deputy PM spoke for the first time on the arrests. He revealed that he and the younger leaders jointly decided to use the ISA on the detainees after “all of us were satisfied that the 16 were indeed involved in some nefarious activities as reported by the ISD.” Although the ISD advised immediate action, the younger ministers did consider various reasons for delayed action. But they finally decided to act swiftly. “The compelling reason for moving against them now is this. Communist cells are like cancer cells. They multiply very quickly and infect other healthy parts of the body. If we do not destroy them now, they will destroy us later.” (ST 30/7/87)

Earlier, the lone opposition member in Parliament, Mr Chiam See Tong had proposed a motion calling for the immediate release of the remaining 15 detainees, and spoke one hour on the issue. Amidst jeers and interruptions by the other MPs, he said that the PAP had a track record for “over-exaggerating” the threats to Singapore and being melodramatic about them. The “scare tactics” of the 50s and 60s would not work today. He argued that the government failed to prove its case against the 15 whose only “crime” was that they were against the PAP. “They are young idealists and intellectuals. They are like you and me…There is no valid reason to detain them for even one more day.” After all, the government had extracted “all the political benefits” it could from the arrests. The government was so certain earlier that the mastermind of the conspiracy was Tan Wah Piow, and now it was touted to be “unseen hands”. If the government was pointing fingers at the CPM, the government should remember that the CPM was “now in shambles” and did not pose a threat to Singapore. “Where is the danger posed by those arrested?” he asked. His motion was shot down. (ST 30/7/87)

Minister Jayakumar countered Chiam’s proposition. He said the detainees were not harmless, innocent people. The CPM network still exists in Singapore, he claimed, Singapore is vulnerable to foreign influences. He added that Vincent Cheng and others in his group were exposed to Filipino communism: “We know that religious organisations were being captured by the communists. We know that sooner or later it was going to affect Singapore and other countries. It happened sooner than we thought.” (ST 30/7/87)

Meanwhile in prison, the detainees were transferred from the tiny 6 x 10 feet cell to share the bigger cells with one or two other detainees. Two-day old Straits Times newspapers were allowed for reading, so were books brought in by family members at the weekly visits and vetted by the ISD. The Catholic detainees were allowed a weekly half-hour worship session with the prison chaplain. Some detainees acted on their right to make legal representations to the Advisory Board against the wishes of the ISD while a few others considered further legal action of habeas corpus at the courts.

August 1987

After the warnings and explanations of the past month, the government would thenceforward press ahead with its stamp of control over the power of religion.

At the eve of National Day broadcast on 8 August, PM Lee devoted the second half of his speech to the issue of religion and politics. Using the Catholic Church and its response to the Marxist conspiracy as an example, he said: “I had always considered the Catholic Church a natural ally against the communists with their anti-God ideology. After this experience, I do not expect the Catholic Church to allow any Catholic priest or Catholic lay worker again to make use of the Church or para-church organisations for political ends. I expect that to be the case with other Christian denominations and indeed with all other religions.” He added that the government was “completely neutral between different religions,” and the existing religious harmony must not be threatened by the mixing of religion and politics. Otherwise a clash of political views could easily turn into a clash of religious beliefs. (ST 9/8/87)

At his National Day Rally Speech on 16 August, PM Lee again devoted part of the speech to repeat his warning to religion to stay in its own domain. He said that Catholic priests and Christian pastors who returned from studies overseas where the Church was a political force should harbour no illusion about going beyond religious activities into “social action”. “Once religion crosses the line and goes into what they call social action, liberation theology, then we are opening up Pandora’s Box in Singapore”. He added that there was always the danger that if one religion did that (mixing religion and politics), others would not want to be outdone, thereby dismembering our multi-religious community. He issued a warning to religious leaders: “Churchmen, lay preachers, priests, monks, Muslim theologians – all those who claim divine sanction or holy insights – take off your clerical robes before you take on anything economic or political…Take it off. Come out as a citizen or join a political party, and it is your right to belabour the Government…But you use a church or a religious publication and your pulpit for these purposes and there will be serious repercussions.” (ST 17/8/87)

On 14 August, S Rajaratnam, Minister of Foreign Affairs and PAP ideologue, gave a religious speech entitled “Is God a Liberation Theologian?” at a NUS Student Forum. This speech was a development of the advice PM Lee gave to the Church to stay in its own domain. Quoting liberation theologians out of context here and there, Rajaratnam belaboured his belief that liberation theology was Marxism spoken in a theological language. He said that “liberation theology has nothing to do with God but with politicised priests, ambitious bishops and smart communists” who needed a new explanation to their efforts to destabilise the world. He compared them to “an expendable army of useful idiots” flocking to join the communist crusade. This recent plot, he propounded, was only the first of many more to come in the region. (ST 15, 20/8/87)

Citing his disdain for westerners who on the basis of human rights supported “disguised Marxists”, Rajaratnam also revealed that the Government had so far received some 400 telegrams from western countries protesting against the recent arrests. Among them was a letter signed by the chairman of the US House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee and 54 other congressmen from both the Republican and Democratic parties, urging that the detainees either be tried promptly or released. The copy of the letter was released by Asia Watch, a Washington-based human rights organisation, and the Straits Times reported it on 21 August 1987.

September 1987

Unexpectedly, the government began to release several detainees who were slated for one-year detention. The Home Affairs Ministry said the government was satisfied they were unlikely to resume subversive activities and become a security threat. The first two to be released on 12 September were Chew Kheng Chuan and Tang Fong Har. Two weeks later, on 26 September, seven more were released: Teo Soh Lung, Wong Souk Yee, Kevin de Souza, Tan Tee Seng, Low Yit Leng, Chung Lai Mei, and Chng Suan Tze. All of them had the usual restrictions upon release.

October 1987

The foreign press was a thorn in the government’s side. Asiaweek, the Hong Kong-based weekly news magazine refused to publish in full the government’s replies to its reports on the arrests. The government thereby accused it of engaging in the domestic politics of Singapore and restricted its circulation in Singapore to 500 copies from the 10,000 copies regularly sold.

The government was indeed concerned about the four priests identified by PM Lee at the Istana meeting as the real troublemakers. The Straits Times published in mid-October their current whereabouts, particularly of Fr. Edgar D’Souza who had fled to Australia.

Amidst the concerns generated by Operation Spectrum in Singapore, citizens were further inundated with news of a similar ISA exercise in Malaysia, codenamed Operation Lalang, on 27 October 1987. 106 persons including politicians, educationists and social activists were arrested by the Mahathir government.

November and December 1987

Fr. de Souza’s relationship with a woman was to become for the following months the premier subject of the government to justify its case. Why it did so with such vehemence came from its claim that Fr. de Souza was conducting an overseas campaign for the detainees. November and December saw long statements and counter-statements from the government, the Church and Fr. de Souza himself. In mid-December Fr. de Souza announced his resignation from the priesthood.

Meantime, the remaining 6 detainees in prison were left in limbo as to their date of release. Then on 20 December, 5 were released at 3pm. They were William Yap Hon Ngian, Kenneth Tsang, Teresa Lim Li Kok, Chia Boon Tai and Tay Hong Seng. Only Vincent Cheng remained in detention, being the only detainee in the whole prison.

Not all was quiet on the news front either. The Far Eastern Economic Review, another Hong Kong-based weekly news magazine, in its Dec 17 issue, made allegations of Church-Government tensions in its article entitled “New Light on Detentions”. It claimed that the article was based on recent statements made by Fr. De Souza. The government decided on 26 December to restrict the FEER to 500 copies per issue in Singapore. PM Lee, through his lawyers, Lee & Lee, also demanded an apology, retraction of the allegations and damages.

The Re-Arrest – 19 April 1988

On 18 April 1988, 9 of the 22 people arrested last year issued a joint statement, denying their ever being involved in a Marxist conspiracy against the state and revealing that they were harshly treated during detention and coerced into confessing on television. The 9 were: Teo Soh Lung, Tang Lay Lee, Kevin de Souza, Kenneth Tsang, Wong Souk Yee, Chng Suan Tze, William Yap Hon Ngian, Ng Bee Leng and Tang Fong Har.

The next day, 19 April, eight of the nine signatories were re-arrested. Tang Fong Har missed arrest as she was in Britain. Lawyer for some of the detainees, Patrick Seong Kwok Kei, 34, was also arrested. The government justified the re-arrest in a statement that it is extremely likely that the ex-detainees would return to conspiring to overthrow the state. It claimed the government had new evidence to show the involvement of the Communist Party of Malaya in the conspiracy. The government also announced that a Commission of Inquiry would be heldto look into allegations made in the statement.

The Singapore Democratic Party and the Workers Party condemned the re-arrest and called for a Commission of Inquiry to look into the allegations by the detainees. Overseas organisations such as Amnesty International and the Australian Catholic Bishops’ Committee for Justice, Development and Peace also called into question the use of the ISA to inflict human rights abuses and torture.

The re-arrested detainees were subjected to unduly harsh psychological duress, with long hours of interrogation in cold rooms and sleeping in claustrophobic cells. The ISD was now inclined to refrain from physical torture. The prison doctor would examine each detainee before and after interrogation. Finally, all detainees (including those who didn’t participate in signing the statement) were required to sign a statutory declaration to admit to the non-existence of ill-treatment in detention and the lack of coercion in interrogation. This new tactic gave the government justification to announce on 28 April that a Commission of Inquiry was no longer needed. The statutory declaration would also inhibit detainees from future attempts to expose ill-treatment or coercion.

May 1988

Unlike in the first arrest, detainees were now agitated towards legal action. On 6 May, the Court adjourned hearing of applications for writs of habeas corpus by Ng Bee Leng, Tang Lay Lee, Kevin de Souza, Wong Souk Yee, Chng Suan Tze, Teo Soh Lung and Patrick Seong. William Yap withdrew his application.

On 6 May, Francis Seow Tiang Siew, 59, the lawyer for Teo Soh Lung and Patrick Seong, was arrested when he came to visit his clients at the Detention Centre. The next day, the Government declared that Seow was arrested for questionable activities with US diplomat, E. Mason Hendrickson. It claimed that Hendrickson had met with anti-government lawyers “to manipulate and instigate Singaporeans, in order to bring about a particular political outcome”. Hendrickson was expelled by the government on 7 May for meddling in local politics; in retaliation, the US government expelled a similarly ranked official of the Singapore Embassy.

On 8 May, Chew Kheng Chuan was re-arrested for helping to draft and distribute the public statement of the detainees. With the arrest of several lawyers and the fears facing other lawyers, detainees had to resort to hiring Queen’s Counsels to represent them.

On 18 May, Justice Lai Kew Chai heard and dismissed applications for writs of habeas corpus by Tang Lay Lee and Ng Bee Leng who were both represented by QC Geoffrey Robertson. On 19 May, both were released with Restriction Orders. Patrick Seong was also released but unconditionally.

On 25 May, Justice Lai Kew Chai heard and reserved judgment on the application for writs of habeas corpus by Kevin de Souza, Wong Souk Yee and Chng Suan Tze. Their lawyer, QC Geoffrey Robertson challenged the validity of the re-arrests on the grounds that the Minister had acted irrationally and in bad faith and also that he had exceeded the powers given him by the ISA. Senior State Counsel S. Tiwari, representing the Home Affairs Minister, the Commissioner of Police and the Attorney-General, contended that the grounds for detaining anybody under the ISA could not be reviewed by the courts because the decision to detain rested solely with the Home Affairs Minister. (ST 28/5/88)

On 27 May, Justice Lai delivered judgment and dismissed their applications.

In parliament, opposition MP Chiam See Tong moved an amendment calling for a rejection of the government’s recent action against the detainees, US government and foreign interest groups, and calling upon the government for more openness and tolerance of legitimate pressure groups. On 27 May, PM Lee gave a lengthy reply to Chiam, justifying the ISA and detention without trial to contain the communists, why he had to step in the Catholic Church’s management of the affair, and why the ISD was Singapore’s greatest asset. He said that the PAP government was not ashamed of what it had done in the Marxist conspiracy and Hendrickson affair.

In Hong Kong, former President Devan Nair called on PM Lee to step down. “All old men develop obsessions,” he said, referring to Lee’s strong concerns with security and law and order in Singapore. “These are the obsessions of an old man. He thinks he’s indispensable.” (ST 29/5/88)

Meanwhile, Archbishop Gregory Yong acted to stop all parish religious services that had been conducted weekly for the detainees.

June – November 1988

During the following months, detainees were busy taking legal actions to secure their release while the government was kept busy on the issue of the forthcoming general elections. On 9 June, representations to the Advisory Board were made by Vincent Cheng, Teo Soh Lung, Kenneth Tsang, Wong Souk Yee, Kevin de Souza, William Yap, Chng Suan Tze and Chew Kheng Chuan.

Surprisingly, on 19 June, William Yap was released on Restriction Order while Teo Soh Lung, Kenneth Tsang, Wong Souk Yee and Kevin de Souza on 20 June had their Detention Order extended for another year. Chng Suan Tze and Chew Kheng Chuan also had their Detention Order extended for one year on 19 July.

From 27-30 June, Teo Soh Lung, represented by QC Anthony Lester, had her habeas corpus case heard before Justice Lai Kew Chai. The court was attended by international observers and many plainclothes police. QC Lester made it known to the court that if he failed to persuade the court to depart from the existing local case law which accepted the Executive as the sole judge in preventive detention cases, Teo would pursue the case to the Privy Council. After the 4-day hearing, Justice Lai reserved judgment.

On 2 August, he dismissed her application. Teo appealed and the case was heard from 26-29 September before Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, Justice L.P.Thean and Justice Chan Sek Keong. She was again represented by QC Lester. The Appeal Court reserved judgment.

From 24-25 October, the same Court of Appeal heard the appeal case of Kevin, Souk Yee and Suan Tze. They were represented by QC Geoffrey Robertson.

The Appeal Court also reserved judgment.

On the other side of the spectrum, Francis Seow was served with a one-year Detention Order on 5 June. But by 16 July, he was released on a Suspension Direction with Restrictions. He had been incarcerated for 72 days. In a statement issued after his release, he revealed that “the Government has extended to me an invitation to contest the next General Election. It would be truly churlish not to accept the invitation even though the Government has mined the road there with obstacles and hazards.” He did stand for election under the Workers’ Party platform on 3 September, and lost by only less than 1% of the votes. He was qualified then to take up the post of Non-Constituency Member of Parliament but before he could take his parliamentary seat, he was forced to flee and live in exile in the United States.

8 December 1988

The Appeal Court delivered its landmark judgment on judicial review. After considering recent Privy Council decisions, the Court held that the Judiciary could review whether the Executive’s decision to arrest suspected subversives was reasonable and based on evidence acceptable in court. This landmark judgment altered principles set some 20 years ago that Executive discretion in ISA cases was absolute and beyond judicial review except in procedural matters. (BT 26/1/89). The Appeal Court allowed all four detainees’ appeals on technical grounds. The four detainees were thereby released at the gates of the Detention Centre but were immediately re-arrested and served with new Detention Orders.

All four detainees filed fresh application for writs of habeas corpus. The legal process was started all over again.

January 1989

The PAP government was not pleased with the latest court decision and worked to reverse it. Law Minister Jayakumar said that the government’s powers to deal with subversion could not be based on legal judgments of foreign judiciaries but must be based on Singapore’s context. With its parliamentary majority in Parliament, it sought changes in legislation. On 25 January, Parliament passed amendments to the Singapore Constitution and the Internal Security Act.

The right of appeal to the Privy Council on ISA arrests was abolished. The power of the judiciary to review ISA cases was revoked and restricted to verifying procedural requirements only. The constitutional amendments stipulated that the provisions dealing with special powers against subversion could be interpreted in whatever way laid down by Parliament, even if the interpretation violated the principle that judicial powers lie exclusively with the courts. (ST 7/3/89).The amendments came into effect on 30 January, in time to jeopardise the legal struggles of Teo Soh Lung.

Despite the latest legal changes, Teo Soh Lung, Chng Suan Tze, Wong Souk Yee and Kevin de Souza made representations to the Advisory Board on 28 January. They also applied for writs of habeas corpus to challenge their detention.

February 1989

Kenneth Tsang and Chew Kheng Chuan, both of whom did not pursue legal suits, were released on 20 February on Suspension Direction, with the usual Restrictions. The Home Affairs Ministry issued the statement saying that “they have responded positively to rehabilitation” and “the Government is satisfied that they are unlikely to resume subversive activities and no longer pose a security threat.”

On 24 February, Chng Suan Tze, Wong Souk Yee and Kevin de Souza withdrew their application of writs of habeas corpus. On 11 March, they were released on Suspension Direction, with the usual Restrictions.

March 1989

From 6-9 March, Teo Soh Lung, represented again by QC Anthony Lester, pursued her third attempt at obtaining release. Appearing before Justice F.A. Chua, the QC questioned the recent changes made to the ISA and the Constitution, saying the amendments were made in bad faith and invalid. He warned of grave consequences if there were no implied limitations to Parliament’s power to amend the constitution. He submitted that Teo’s detention was unlawful.

Justice Chua reserved judgment. On 25 April, Court dismissed Teo’s application for writ of habeas corpus. She filed appeal.

On 11 March, The Straits Times reported that QC Anthony Lester had been barred by the Government from working in Singapore on the grounds that he had engaged in Singapore’s domestic politics by commenting overseas that democracy and the independence of the judiciary were being undermined both in Malaysia and in Singapore with regard to ISA.

April 1989

By April, only Teo Soh Lung and Vincent Cheng were still detained at Whitley Centre.

On 22 April, Vincent made his second representation to the Advisory Board.

June 1989

On 20 June, Vincent Cheng and Teo Soh Lung’s Detention Orders were extended for another year.

Kevin de Souza, Kenneth Tsang and Wong Souk Yee’s Suspension Direction expired and were replaced with 2-year Restriction Orders.

Mah Lee Lin’s 1-year Restriction Order lapsed.

On 21 June, Vincent Cheng applied for writ of habeas corpus.

September 1989

On 1 September, Vincent Cheng, represented by lawyer Patrick Seong, made a request to cross-examine the Home Affairs Minister, its Permanent Secretary, the ISD Director and 4 other ISD officers at his forthcoming court hearing. The judge rejected his request in chambers and ordered him to pay costs.

From 11-15 September, Vincent’s habeas corpus writ was heard before Justice Lai Kew Chai. He was represented by QC Michael Beloff who argued that: Vincent was not involved in an anti-government plot, he was practising his Christian faith, no evidence to justify Vincent’s detention, and the recent amendments to the Constitution and ISA were invalid.

The judge reserved judgment.

On 31 January 1990, Vincent’s application for writ of habeas corpus was dismissed with costs.

October 1989

On 2 October, PM Lee made clear his thoughts about the ISA to questions from QC Geoffrey Robertson. He said that no amount of human rights agitation would succeed in pressurising the Government to give up its powers under the Internal Security Act or to release detainees. He reiterated that in ISA cases, the Government was not obliged to give evidence in a court of law. As for the role of the Church, Mr Lee said he had described “in graphic terms” to Archbishop Gregory Yong that if agitation within the Church for the release of the detainees was allowed to go unchecked, it would lead to civil disorder. (ST 3/10/89).

November 1989

From 13-16 November, the Court of Appeal comprising Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, Justice L.P. Thean and Justice Chan Sek Keong heard the appeal of Teo Soh Lung, represented by QC Lord Alexander. The QC said that if the court disagreed with his submission that the executive could only act within the scope of powers as conferred by Parliament, it must logically follow that the government was invested with an ‘arbitrary power’ to arrest and detain, which was not limited in national security purposes. The amendments would then be unconstitutional.

The Appeal court reserved judgment.

On 3 April 1990, the Court dismissed with costs Soh Lung’s fourth attempt to be freed.

June 1990 – Freedom At Last!

On 1 June, Teo Soh Lung was released with Restrictions. Her one-year detention order, due to expire on 19 June, was suspended on the ground that the Government was now satisfied that “she has been rehabilitated enough to be released.”

On 20 June, Vincent Cheng was released with Restrictions. He had to sign 3 conditions before release, namely that he would not promote communism in Singapore, that he would not use religion for politics, and that he would obey six restrictive conditions upon release.

The six restrictions are:

(1) that he shall not travel beyond the limits of Singapore without the prior written approval of the Director, Internal Security Department, Singapore.

(2) that he shall not knowingly associate or be in communication with any person who is currently or has previously been detained under the Internal Security Act of the Federation of Malaya, Malaysia or Singapore, except with members of the Singapore Ex-Political Detainees’ Association, provided he is also a member of such association.

(3) that he shall not knowingly associate or be in communication with any person who is connected with Marxist or communist organisations or their front organisations, or any organisation implicated in the Marxist conspiracy as enumerated in the MHA press statement of 26 May 87.

(4) that he shall not issue public statements, address public meetings, or print, publish, distribute or contribute to any publication without the prior written consent of the Director, Internal Security Department, Singapore.

(5) that he shall not hold office in, or take part, or in any way assist in the activities of or act as adviser to, or be a member of any organisation, association, or group without the prior written consent of the Director, Internal Security Department, Singapore.

(6) that he shall report to the Internal Security Department on the first working day of every month at a time specified by the Director, Internal Security Department.

A Suspension Order suspends the operation of a Detention Order, subject to the detainee executing a bond, and subjects him/her to conditions similar to those in a Restriction Order.

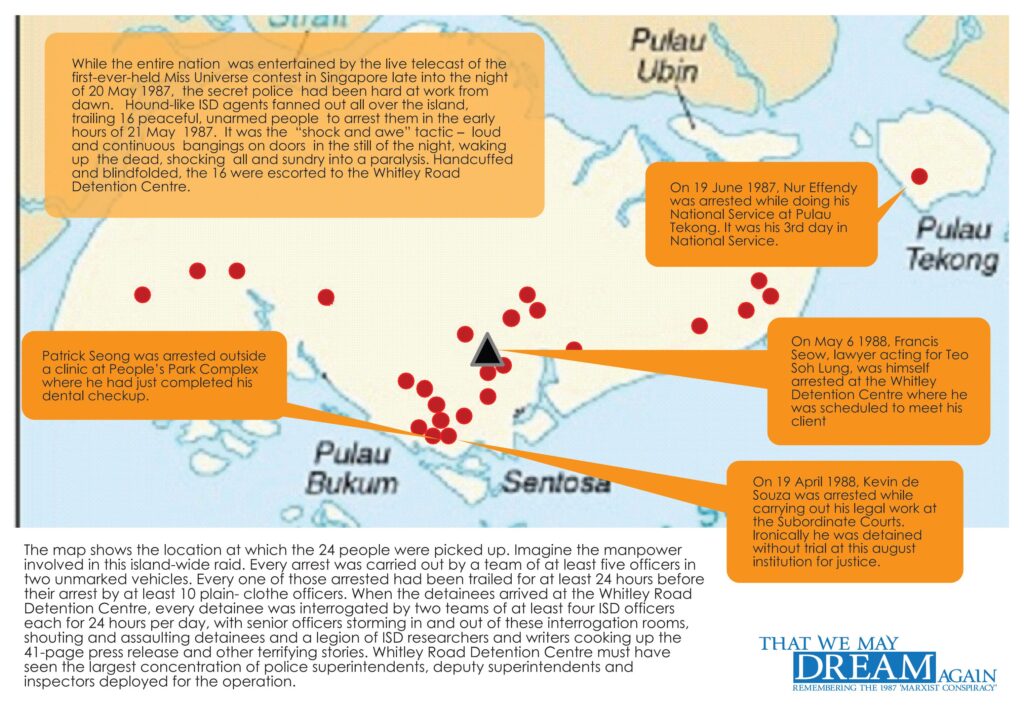

(Main text) The map shows the location at which the 24 people were picked up. Imagine the manpower involved in this island-wide raid. Every arrest was carried out by a team of at least five officers in two unmarked vehicles. Every one of those arrested had been trailed for at least 24 hours before their arrest by at least 10 plain- clothe officers. When the detainees arrived at the Whitley Road Detention Centre, every detainee was interrogated by two teams of at least four ISD officers each for 24 hours per day, with senior officers storming in and out of these interrogation rooms, shouting and assaulting detainees and a legion of ISD researchers and writers cooking up the 41-page press release and other terrifying stories. Whitley Road Detention Centre must have seen the largest concentration of police superintendents, deputy superintendents and inspectors deployed for the operation.

(text in orange boxes in clockwise direction)

While the entire nation was entertained by the live telecast of the first-ever-held Miss Universe contest in Singapore late into the night of 20 May 1987, the secret police had been hard at work from dawn. Hound-like ISD agents fanned out all over the island, trailing 16 peaceful, unarmed people to arrest them in the early hours of 21 May 1987. It was the “shock and awe” tactic – loud and continuous bangings on doors in the still of the night, waking up the dead, shocking all and sundry into a paralysis. Handcuffed and blindfolded, the 16 were escorted to the Whitley Road Detention Centre.

On 19 June 1987, Nur Effendy was arrested while doing his National Service at Pulau Tekong. It was his 3rd day in National Service.

On May 6 1988, Francis Seow, lawyer acting for Teo Soh Lung, was himself arrested at the Whitley Detention Centre where he was scheduled to meet his client.

On 19 April 1988, Kevin de Souza was arrested while carrying out his legal work at the Subordinate Courts. Ironically he was detained without trial at this august institution for justice.