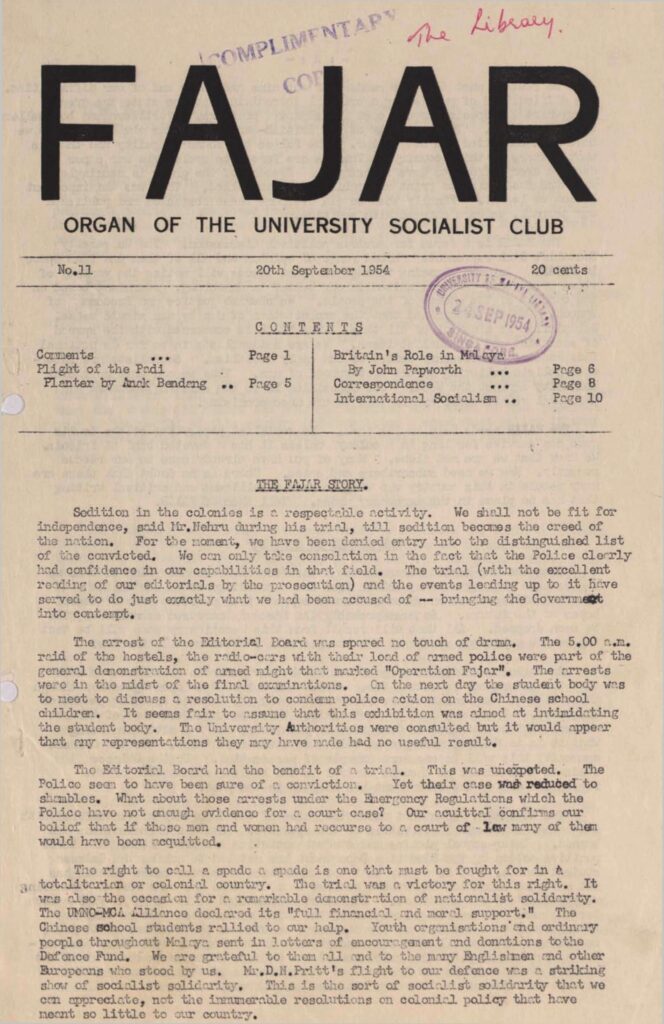

The Fajar Story in Fajar 20 Sep 1954 No.11

从华惹诉讼到华惹世代 – 傅树介(林康 译)

This year, 2024, marks the 70th anniversary of the editorial ‘Aggression in Asia’ in Fajar issue 7, 10 May 1954 which led to the arrest on 28 May of its editorial board members on the charge of sedition. As the president of University Socialist Club, the publisher of Fajar, I was one of the eight defendants, and the point man. I was then a 22-year old 3rd year medical student. Nine years later, at age 31, I was arrested and imprisoned without trial in Operation Coldstore. With a break from December 1973 to June 1976 when I was released on restriction orders, I was rearrested in 1976 and was released when I was 50 years old. At the age of 77, I was one of the editors of The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore (2010).

At 92 years old, I have this opportunity to commemorate the Fajar trial as a landmark in Singapore’s decolonization process.

The Fajar Trial

The Fajar trial changed the course of my life and must have those of my co-defendants as well. The event also altered the course of politics in Singapore which the British colonial rulers had been charting for post-war Singapore.

We had not set out to court arrest and make headlines with ‘Aggression in Asia’. In fact, we were careful to reference prominent British left wing Labour Party leaders in condemning the formation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) as the militarization of the region, evident in the ongoing war by France against Vietnamese anti-imperialism. We contended that Malaya was being turned into a military base for colonial wars which our young men were being conscripted to fight in.

We had no idea that on May 13, three days after the publication of ‘Aggression’ the Chinese middle school students would be attacked by the police for objecting to the registration of school students for national service. We stood with the students. The day before our arrests, the University student body had arranged a meeting to discuss a resolution to condemn the police action against the middle school students. (See ‘The Fajar Story’, no. 11, 20 Sept 1954).

With the Fajar trial and the May 13 police violence “Merdeka” became the most popular and powerful word in Singapore politics for the better part of a decade.

The arrest of University Socialist Club members on the charge of sedition i.e., inciting people to rebel against the authority of the Queen was sensational, but the dismissal of the case by the judge was even more so.

Our lawyer, D N Pritt, QC had represented anti-colonial leaders including Indian revolutionaries, Kenyan independence fighters, and Ho Chi Minh. John Eber, a senior lawyer and a key leader of the defunct Malayan Democratic Union (MDU) who moved to the UK following his release from detention in 1951 under the Emergency Regulations had approached two eminent lawyers to represent us. I went for Pritt, who duly got us to research on sedition cases in the British colonies from Amritsar to Batang Kali. He was going to turn the trial into a political event.

The Emergency and the Fajar Trial

I regard the left in the MDU as our predecessors in the anti-colonial movement. The party, founded following Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, was made up of English-speaking Malayans in Singapore who were opposed to re-colonisation by the British. The MDU attracted young lawyers, Raffles College graduates, clerks, as well as members of the MCP, which had been legalised after the war.

The political space that emerged in the MDU period did not last for long. A state of Emergency was imposed in June 1948. Once again listed as illegal, the MCP waged jungle warfare in the peninsula against the colonial military forces. In October 1949, the People’s Republic of China ruled by the Chinese Communist Party came into being. Repressive political action on the island followed in quick succession. In May 1950, the British managed to smash the Singapore Town Committee, which they alleged directed communist operations. The Chinese High School and Nanyang Girls’ High School were raided by the police and closed for two months with about twenty students arrested under the Emergency Regulations. In 1951, the left-wing MDU members including John Eber, and students of the University of Malaya were arrested. Following the repressive blitz against anticolonial groups, the government was ready to allow its protégés to assume political leadership in a controlled process of decolonisation.

The Rendel Commission was set up in 1953 to work out constitutional provisions for partial self-government. It provided for a legislative assembly with 25 seats for elected members out of 32. The electoral base was expanded, with the majority party forming the government.

In line with the gradual political liberalization, the university authorities had permitted the registration of the Socialist Club in 1953, a standard feature in the elite British universities. However, the limits of what activities would be permissible for the Club was a matter of judgment. Governor John Nicoll (1952-55) a career colonial official for 31 years deemed that the Club was disruptive and potentially threatening. Malcolm MacDonald, governor general (1946-48) and British commissioner general (1948-55) in Southeast Asia, a reformist Labour party politician who took credit for the creation of the University of Malaya in 1949 and was its first chancellor was more liberal. Nicoll decided to charge the Fajar editorial board for sedition; MacDonald had preferred to have the vice-chancellor warn the students about getting into trouble.

In the end, MacDonald’s view that an open trial with Pritt defending was likely to work against the state prevailed. Immediately after our acquittal without defence being called, I received a phone call from his office with an invitation for dinner. No doubt, photos of the two of us enjoying each other’s company would be splashed in the newspapers, wiping out the anti-colonial effects of the Fajar trial. I did not oblige him.

On the same day of our arrests on 28 May, the director of education summoned the school management committees and principals of the key Chinese middle schools and demanded greater control over the students, the enforcement of greater disciplinary training, the re-registration of all students, and the expulsion from school of students of call up age who had not registered for national service.

The students of the University of Malaya and the Chinese high schools, the highest level education institution for the two language streams, had found one another thanks to the persecution by the colonial authorities. We were a new energetic political force of younger generation on the left. In the 1955 elections less than a year later, the pro-colonial party was decimated.

Fajar: The Hock Lee riots

In his 2008 tribute to commemorate the passing of M K Rajakumar, my closest friend and comrade and the key person behind ‘Aggression in Asia’, Tan Jing Quee observed that the 1954 trial had “catapulted” Fajar into “a major left-wing journal in the country”. Fajar kept abreast with socialism and developments in the socialist world, published essays on race and political economy in Malaya, and scrutinized ongoing political moves and events in Singapore. Today, this “major left-wing journal in the country” has become a valuable documentary source on the debates and issues in Singapore’s history that have been silenced until the last one and a half decades. The history of the 1950s and early 1960s imposed by the ruling party to this day has been no more than the relentless labeling of its opponents as communists.

Fajar’s tracking of the Hock Lee riots as events unfolded demonstrates the Club’s engagement as a grounded, critical voice alert to the wiles and lack of scruples on the part of the colonial power and its local collaborators. Its analysis of the May 12 1955 Hock Lee riots is one of its most incisive on the 1950s. (See ‘Crisis in the Left’, Fajar, no. 19, May 31 1955). As the country’s first chief minister, David Marshall had moved the motion in the first Legislative Assembly sitting on 22 April 1955 that in three months’ time, his government would decide whether the main provision in the Emergency Regulations which provided for detention without trial was necessary. Fajar discerned from this that “the riot was used as a propaganda weapon to prevent the Government from carrying out the promised reform of the Emergency Regulations”.

Indeed, with the Hock Lee riots, the government passed the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance (PPSO) in October 1955 which retained detention without trial. On top of that, the Ordinance would be in force for three years, instead of three months under the Emergency Regulations.

Fajar’s analysis is highly pertinent. It would not make sense for “communist instigators” to derail Marshall’s declared aim of reviewing the Emergency Regulations by fomenting chaos and violence at this time. It was the colonial power and its collaborators who benefitted from the riots.

Fajar: ‘Merger and Malaysia’

Tan Jing Quee’s essay ‘Merger and Malaysia’ in Fajar December 1961 (Vol lll no. 8) makes sense of Federation of Malaya prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman’s surprise declaration of support on 16 October 1961 for Singapore to be included in a merger with Malaya, and the Borneo states and explores why the Singapore government would agree to the terms of merger which were clearly unfavourable for Singapore.

The so-called “Battle for Merger” is the most cynical and diabolical manipulation of politics and massive wielding of the PPSO on trumped up charges that Singapore has witnessed. Debates in the Legislative Assembly were unabashed displays of Cold War rhetoric against the left, the obfuscation of facts on crucial issues such as nationality and citizenship, and the hollowness of Singapore’s autonomy over labour and education given that they were subject to the overall supervision of internal security by the Federal government. Tan observed that the “freak arrangement” that was merger was to bail out the PAP government. The political fortune of the PAP had been hinged on anti-colonialism, but once in power, the party abandoned its mass base, relying instead on British patronage and alliance with the right wing government of Malaya to destroy its erstwhile powerful left wing forces.

This came to pass with Operation Coldstore. Along with the mass arrests, was the ban on Fajar.

‘Merger and Malaya’ reached the heart of the merger issue which the left, led by the Barisan Sosialis of which I was the deputy to secretary general Lim Chin Siong warned against. We were bombarded relentlessly with accusations of being communists, sham debates in the Legislative Assembly, a blatantly biased media including the sensational ‘Radio Talks’ series, fear-mongering, and the most unscrupulous ‘referendum’ that could be conceived. The wonder of it is that till today, the PAP takes great pride in its chicaneries and deceit despite the failure of merger within two years.

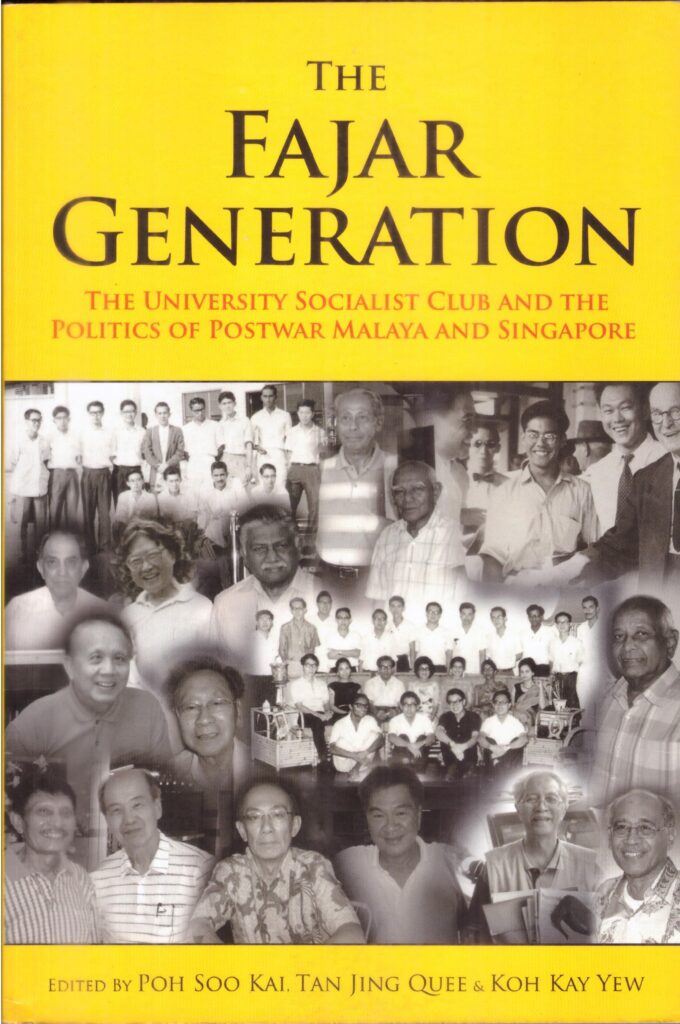

The Fajar Generation

The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of postwar Malaya and Singapore, published in 2009 brought Fajar back into public consciousness. I was the editor, along with Tan Jing Quee and Koh Kay Yew. We served as the Club’s president in 1954/1955, 1961/62, and 1965 respectively.

If not for Tan Jing Quee, we would not have this book today.

I had spent much of the long years in prison reflecting on how my comrades and I constituted threats to the dominant ruling party, and the prevailing international world order. On my release, I realised that there were no avenues to fight for accountability for the injustice done to us. We had to take a long term view. I headed to the UK National Archives in 1993, when the documents of the period up to 1963 entered the public domain with the expiry of the period of embargo. I read every file from 1956 and shared my photocopies and notes with Tan Jing Quee, Koh Kay Yew, M Rajakumar and Lim Hock Siew. We had extensive discussions, but did not go beyond that.

A breakthrough came when Michael Fernandez and Tan Jing Quee presented a talk at February 2006 fringe arts festival event with the theme Detention-Writing-Healing. The audience of largely young people had no inkling of what political imprisonment in Singapore was about. Jing Quee explained that political prisoners in Singapore were worse off than convicted criminals for they were not allowed to defend themselves in a court of law, and their imprisonment could be renewed every two years without limit.

The minister of home affairs responded with a warning: “ex-political detainees will not be permitted to rewrite history”.

Following the talk, Jing Quee started planning on a book on the University Socialist Club. He visited me a good number of times to urge me to participate. Each time, I did not give him a commitment. I did not say so, but I was afraid of being re-arrested.

On the last occasion, he was upset, and abruptly walked out of my house.

Jing Quee’s wife, Rose, came back in and said, “Soo Kai, please write”.

I agreed to do so, realizing just how much the project meant to him.

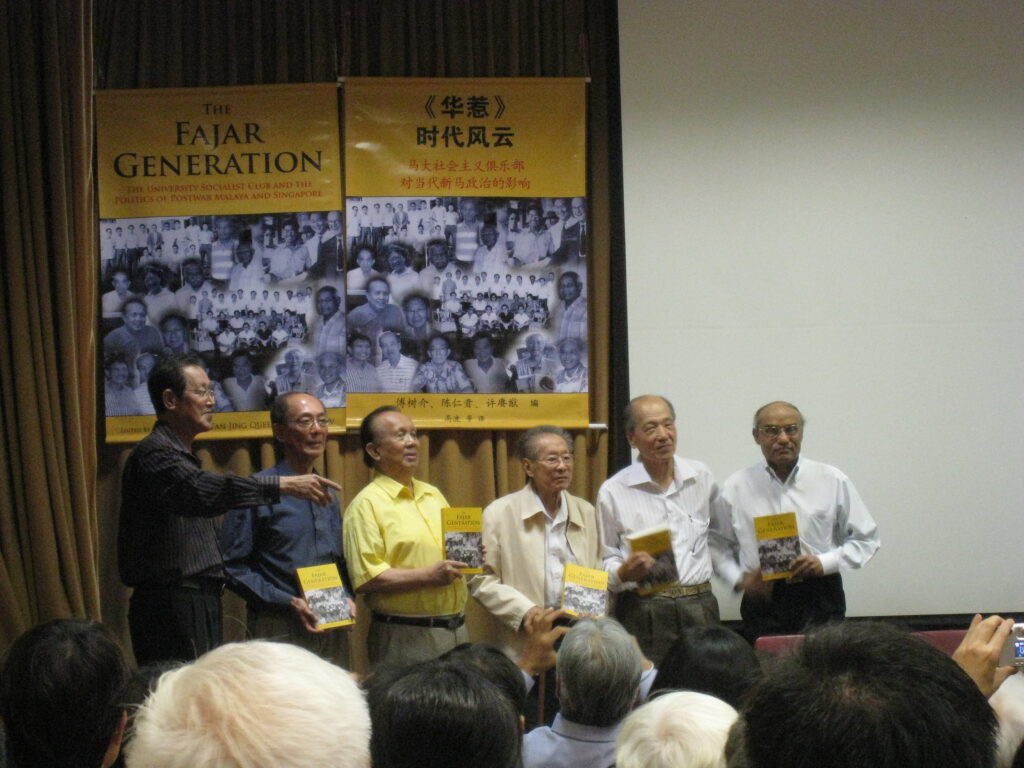

The launch of the book on 14 November 2009 was carefully planned. We decided that it would be held in Singapore and the venue was made known only at the last minute. My speech was a rambling one, full of innuendoes which the audience had trouble following.

But a barrier had been broken. As Jing Quee said to me, “No one would have believed that a medical doctor and a blind man could publish this book”.

At the book launch in Penang two months later, I found myself declaring spontaneously in response to a question from the audience: “We are not re-writing history. We are writing history”.

We have not looked back since.

The Fajar Generation

At 92, I am the oldest surviving member of the Fajar generation who are Singaporeans, with the exception of Michael Fernandez who is a year older, but there are a number of seniors who are Malaysians. At this age, one’s circle of friends gets smaller by the day. Just this week, I was informed that Socialist Club member Agoes Salim had passed away in Kuala Lumpur (15 March 2024). Agoes had contributed a brief sketch of his Socialist Club activities in The Fajar Generation. He recalled that he went around the student hostels collecting money for the bus workers in a big tussle with the employers, and helped the PAP campaign in the 1955 general election. He was president of the USC in 1956. An economist, he served in senior positions in the Malaysian government. We met from time to time in KL. He was always comradely.

The attrition of time will continue to take my USC comrades away. The youngest would now be around 80 years old. Among them, is fellow editor Koh Kay Yew who phones regularly, and visits when he is in Malaysia. With him, I can discuss theoretical issues on socialism and critiques of the neo-liberal economy. We go back such a long way.

I have also renewed friendships with so many people since The Fajar Generation. Tan Kok Chiang and his brother Kok Fang, friends since the May 13 days when they were in the Chinese middle school anticolonial movement were editors respectively of The May 13 Generation: The Chinese Middle Schools Student Movement and Singapore politics in the 1950s (2011), and The 1963 Operation Coldstore in Singapore: Commemorating 50 years (2013). Both titles were the initiative of Tan Jing Quee, and are sequels, so to speak, of The Fajar Generation. Kok Fang has made countless speeches at public gatherings when he was invited to speak. They have also translated our writings and speeches, being effectively bilingual.

There are also Barisan, labour union and other former political prisoners, some of whom were a little younger and mainly Chinese-speaking—part of the “Old left”. We have renewed our friendships, and they have introduced me to new friends, some of whom have visited a good number of times, one group packed in a mini bus. They discuss how to keep our socialist ideas and spirit alive in Singapore today.

Having our history in writing has made us proud of our past and helped rebuild solidarity after decades of silence and isolation. We have consolidated ourselves into a Generation, so apt a term that Jing Quee employed.

Fajar Generation+

More importantly, the Fajar generation is not limited only to those who were in the forefront of political activism in the 1950s and early 1960s and imprisoned under the Internal Security Act. I regard as Fajar generation+ those younger people that I have come to know through the decades, who in their own ways have a principled stand and taken action against injustices and exploitation, pitting themselves against the powerful status quo. I am convinced that no matter how bleak, there has been and will continue to be, Singaporeans who will stand up for secular human values, justice and peace and who value our history and shared vision.

今年( 2024 年),是《华惹》(Fajar)第 7 期(1954 年 5 月 10 日出版)社论《对亚洲的侵略》(Aggression in Asia)发表 70 周年,该社论导致《华惹》编辑委员会一众成员于当年 5 月28 日因煽动叛乱罪被捕,随后被起诉。 身为大学社会主义俱乐部主席、俱乐部会刊《华惹》出版人,我是八名被告之一,是当中的领头羊。 我当时22岁,大学医学院三年级学生。 九年后,我31 岁,在“冷藏行动”(Operation Coldstore)中被未经审判拘捕下狱。经过1973年12月至1976年6月期间(在强加限制令下获释)的短暂自由后,我在1976年重新被捕,直至年届50岁才被释放。我77岁时,《华惹世代:大学社会主义俱乐部以及战后马新政治》(The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore)一书出版,我是该书编辑之一。

如今我已达92岁高龄,庆幸自己仍有机会纪念华惹诉讼案。新加坡去殖民化进程中,这是一个里程碑。

华惹诉讼

华惹诉讼案改变了我,想必也改变了我那些共同被告友人们的一生。 该事件也改变了英国殖民统治者为新加坡所制定的战后政治进程。

我们并未预料到会因为发表《对亚洲的侵略》一文而被捕,并成为头条新闻。事实上,我们在谴责东南亚条约组织(SEATO)的成立时,小心翼翼地引用了英国左翼工党著名领导人的相关言论,认为这是促使地缘军事化的步骤,从法国正在进行镇压越南反帝国主义运动的战争中体现出来。 我们争辩指出,马来亚正在变成殖民战争的军事基地,我们的青年被征召入伍参战。

我们也无法预知,5月13日,《对亚洲的侵略》发表三天后,华校中学生会因为反对在籍学生完成兵役登记而遭到警方袭击。 我们和中学生们站在一起。 在我们被捕前一天,大学学生会开会,讨论谴责警方暴力对待中学生的议决案。(参见《华惹》第 11 期,1954 年 9 月 20 日出版)。

因为华惹诉讼案和 513 警察暴力事件,“孟迪卡”(Merdeka,独立),从此成为新加坡政坛近十年里最流行、最具影响力的口号。

以煽动叛乱罪(即煽动人民反抗皇室权威)逮捕起诉大学社会主义俱乐部成员引起轰动。而此案在法庭遭法官驳回,引起更大的轰动。

帮我们辩护的丹尼斯·普里特( D N Pritt)女皇律师,曾是各地反殖领袖,包括印度革命者、肯尼亚独立战士和胡志明的代表律师。约翰·埃伯(John Eber),资深律师,已解散马来亚民主同盟 (Malayan Democratic Union, MDU) 主要领导人,1951 年在紧急法规(Emergency Regulations)下被不经审判拘押,1953年获释后移居英国。他为我们物色并联系了两位著名律师。 我选了普里特。普里特让我们研究各英殖民地发生的煽动叛乱案件,从阿姆利则(印度)到峇冬加里(马来亚)。 他打算把法庭上的诉讼变成一起政治事件。

紧急状态与华惹诉讼案

我认为马来亚民主同盟的左派,是我们反殖民运动的先驱。 民盟在第二次世界大战日本战败后成立,由新加坡受英文教育,反对英国回来重新殖民的马来亚人组成。 民盟吸引了年轻律师、莱佛士书院毕业生、文员以及战后合法化的马来亚共产党党员加入。

民盟时期的政治活跃空间没能维持太久。1948年6月殖民当局宣布紧急状态。马共再次被列为非法,在马来半岛对英殖民军队发动森林游击战。 1949年10月,中国共产党领导的中华人民共和国成立。新加坡岛上的政治镇压接踵发生。 1950 年 5 月,英国人成功捣毁了他们声称负责指挥马共活动的星洲市委。 警方突袭搜查华侨中学和南洋女中,两校停课两个月,约二十名学生在紧急法规下被捕。 1951年,约翰·埃伯等民盟左翼成员和马来亚大学学生被捕。 随着出台系列镇压反殖团体的闪电战,殖民当局做好了扶植门徒,安置在受控的去殖民化运动中担任政治领导角色的准备。

1953年林德委员会成立,负责制定与组建部分自治政府相关的宪法条款。根据林德宪制,在立法议会32 个席位中,民选议席占 25 个,借此扩大民选基础,并规定由赢得多数议席的政党组织政府。

和政治的逐步开放相一致,1953年大学当局允许社会主义俱乐部注册,这是英国精英大学的标准特征。 然而,对社会主义俱乐部可从事活动应施加何等限制,则是个决策问题。约翰·尼诰(John Nicoll)总督(1952-55 年),一个31年资历的职业殖民地官僚,认为社会主义俱乐部具有破坏性和潜在威胁。 马尔科姆·麦克唐纳(Malcolm MacDonald)总督(1946-48 年),英国驻东南亚专员总长(1948-55 年),则是一位改革派工党政治家,他因 1949 年创建马来亚大学而广受赞誉,为该大学第一任校长,此人立场相对自由开明。 尼诰决定以煽动叛乱罪起诉华惹编委会;麦克唐纳更希望可由大学校长出面,劝诫学生克制不要惹麻烦。

麦克唐纳担心,由普里特担任辩护律师的公开诉讼过程,可能出现对国家不利的状况。最终,麦克唐纳的观点占了上风。在我们还未被传召辩护就宣判无罪后,我几乎即刻接到了他办公室邀我去吃晚餐的来电。 我们两人惬意一起进餐的照片若出现报端,华惹诉讼案引发的反殖情绪,无疑将很大程度被抵消掉。 我没答应赴约。

5月28日,我们被捕的同一天,教育局局长召集了学校管理委员会和华文重点中学的校长,要求加强对学生的控制,如强化纪律训练,对所有学生实行重新注册,以及将未完成兵役登记的适龄学生开除出校。

马来亚大学和华侨中学,来自两所不同语文源流最高学府的学生,竟由于殖民当局的迫害而找到了彼此。 我们年轻一代由是形成了一股充满活力的新的左翼政治力量。 在不到一年后的 1955 年大选,亲殖民地的政党惨遭碾压。

华惹怎么说:福利巴士工潮

陈仁贵(Tan Jing Quee),我最亲密的朋友与同志,《对亚洲的侵略》一文背后的关键人物,2008年悼念拉惹古玛 (M K Rajakumar)时指出,1954 年诉讼案使《华惹》瞬间成为“当地主要的左翼刊物”。《华惹》紧跟社会主义和社会主义世界的发展局势,发表马来亚种族和政治经济相关的分析文章,密切关注新加坡的政治动向与事态。 今天,这个“当地主要的左翼刊物”成了辩论与了解新加坡历史的宝贵文献来源,重新激活了过去十几二十年来一度沉默的状态。 执政党如今讲述的五六十年代历史,除了给对手无情贴共产党标签外,什么都不是。

《华惹》对福利巴士工潮的追踪报道,反映了大学社会主义俱乐部介入,发出的是接地气而直中要害的声音,有别于殖民当局及其同伙的鬼话与恬不知耻的胡言。 《华惹》对 1955 年 5 月 12日福利巴士工潮的分析,是该刊50 年代最具深度的文章之一(见《左翼的危机》,《华惹》第19 期,1955 年 5 月 31 日出版)。马绍尔(David Marshall),新加坡第一任首席部长,1955 年4 月 22 日在第一届立法议会提出动议,承诺他治下的政府将在三个月内决定,紧急法规(Emergency Regulations)中关于不经审判拘押的条款是否有必要保留。《华惹》从中看出,“福利巴士工潮演变成骚乱,其实是某种宣传武器,旨在阻止政府落实改革紧急法规的承诺”。

事实上,利用福利巴士工潮演变成骚乱,1955 年 10 月政府通过了“维护公共安全法规”(Public Security Ordinance, PPSO),保留了不经审判拘押的条款。 不单如此,该法规下不经审判拘押的有效期为三年,而不是紧急法规中的三个月。

《华惹》的分析鞭辟入里。 “共产党煽动者”发起暴动、制造混乱,来破坏马绍尔审查改革紧急法规的承诺,这简直狗屁不通。骚乱的受益方,恰恰是殖民当局及其合伙人。

华惹怎么说:合并与马来西亚

陈仁贵 1961 年 12 月在《华惹》(第 3 卷第 8 期)发表文章《合并与马来西亚》,解释马来亚联合邦总理东姑阿都拉曼 1961 年 10 月 16 日出人意料宣布支持新加坡、婆罗洲与马来亚合并的声明, 并对新加坡政府为什么会同意显然对新加坡不利的合并条款进行了探讨。

所谓“争取合并的斗争”,是迄今为止新加坡所目睹最讽刺、最邪恶的政治操纵,也是迄今为止新加坡所见证挥舞着维护公共安全的大棒子,肆无忌惮捏造罪名的大规模运作。立法议会的辩论,尽是些赤裸裸针对左派的冷战话术,在国籍和公民身份等关键问题上只能混淆事实颠倒是非,至于新加坡在劳工与教育政策上享有自治权,因为受联邦政府基于国家内部安全而实施的全面掌控,这类自治并无任何实质意义。陈仁贵还观察到,合并这一“奇葩安排”无非为了拯救人民行动党政府。人民行动党的政治前途和反对殖民主义休戚相关,但该党在掌权后就背弃了其群众,转而依靠英国的庇护,与马来亚右翼政府结盟,意图摧毁其昔日坚强盟友的左翼势力。

冷藏行动实现并凸显了该意图。在推进大规模逮捕的同时,《华惹》被查禁了。

“合并与马来亚”才是合并问题的核心,以社会主义阵线为首的左翼对此提出了警告。林清祥是社阵秘书长,我是他的副手。 我们受到了铺天盖地的无情抨击,胡乱指控我们是共产党,立法议会里尽是言不及义的虚假辩论,摆明偏袒的媒体(包括耸人听闻的“广播谈话”系列),散布兜售恐慌情绪,以及不择手段之最的“全民投票”。 奇妙的是,尽管合并在两年内即宣告失败,人民行动党至今仍对其诡计和欺骗行径感到自豪。

《华惹世代》

《华惹世代:大学社会主义俱乐部以及战后马新政治》一书,2009年出版面世,把《华惹》重新带回到公众视野当中。我是该书编辑,其他编辑有陈仁贵和许庚猷。 我们是社会主义俱乐部的先后主席(傅树介,1954/1955年;陈仁贵,1961/62年;许庚猷,1965年)。

要不是陈仁贵,我们今天不会有这本书。

我在漫长的牢狱岁月里,针对我和我的战友们究竟是如何对占据主导地位的执政党,以及现行的国际社会秩序构成威胁的,花了许多时间思考。 获释后,我意识到没有任何途径可以为我们所遭受到的不公待遇追究责任。 风物长宜放眼量。我们只好采取长远的目光。 1993 年,英国前于并截至1963年的档案,保密期限届满解禁,我于是动身前往英国国家档案馆。 我读了 1956 年以降的所有文件,并与陈仁贵、许庚猷、拉惹古玛和林福寿分享了我的复印件和笔记。 我们进行了广泛的讨论,但也仅限于此。

直至2006 年 2 月,迈克·费南德斯(Michael Fernandez )和陈仁贵在艺术节“艺穗”活动上发表题为“拘留-写作-治疗”的演讲,这才打破了僵局。 当时的观众主要是年轻人,对新加坡的政治监禁一无所知。陈仁贵解释说,新加坡政治犯比定罪的罪犯处境更糟,因为他们不被允许在法庭上为自己辩护,而且他们的监禁可以无限期地每两年延续一次。

内政部长以警告对此作出回应:“我们不会允许前政治犯改写历史”。

演讲结束后,陈仁贵开始计划要写一本关于大学社会主义俱乐部的书。他多次拜访我,敦促我参加。 每一次,我都不给他许诺。 我没说出口,其实我害怕重新被捕。

最后一次,他很不高兴,骤然疾步从我家走了出去。

仁贵的妻子 Rose 返回来说:“树介,你写吧。”

这回我答应了。因为意识到这项工作在仁贵心目中的意义。

该书在 2009 年 11 月 14 日发布,这是细心策划的。 我们决定在新加坡举行发布会,但要等到最后一刻才公布地点。 我的演讲乱无章法,充满影射,让听众听得一个头两个大。

但不管怎么说,魔障总算是破除了。 正如仁贵对我说的那样,“没人会相信,一个医生和一个瞎子,竟可以捣弄出版这么一本书”。

两个月后,在槟城的新书发布会上,我发现自己在回答观众提问时自发宣称:“我们不是在改写历史。 我们正在书写历史。”

从那时起,我们再也没有回头。

华惹世代

我今年92岁,是仍在世的华惹世代中年龄最长的新加坡人,迈克·费南德斯除外,他比我大一岁;另外还有不少比我年长的,但都是马来西亚人。 到了这般年纪,朋友圈一天天见缩小。 就在本周,我获悉社会主义俱乐部成员阿戈斯·萨利姆(Agoes Salim)在吉隆坡去世了(2024年3月15日)。 阿戈斯在《华惹世代》书中概要介绍了他自己在社会主义俱乐部的活动。 他回忆说,曾经穿梭走遍学生宿舍,为与雇主激烈抗争中的巴士工人筹款,以及在1955年大选中为人民行动党助选。 他是社会主义俱乐部1956 年的主席。作为一名经济学家,他历任马来西亚政府的高职。我们有时在吉隆坡会面。 他总是表现出同志般的热情。

时间的耗损,将继续带走我社会主义俱乐部的同志们。他们中最小的,现在怕也已经80左右岁了。他们当中的许庚猷,我《华惹世代》一书的编辑伙伴,经常打电话来,到马来西亚时也会来访我。 我和他可以一起讨论社会主义的理论问题和对新自由主义经济的批判。我们毕竟相知了那么久远。

自《华惹世代》出版以来,我跟许多人重新建立了友谊。 陈国相和他的弟弟国防,是513那时的老友,他们当时参与了华校中学生的反殖民运动,分别是《情系五一三:一九五零年代新加坡华文中学学生运动与政治变革》(2011)以及《新加坡1963 年的冷藏行动. — — 50 周年纪念》(2013 年)两书的编辑。该两部书都出自陈仁贵的倡议,可说是《华惹世代》的续作。 陈国防曾多次受邀在公众集会上演讲。他们双语能力都强,很做了些我们书写与演讲的翻译。

还有社阵、工会和其他前政治犯,其中有些年龄稍小,主要讲华语,属于“老友”的部分组成。我们重新建立了友谊,他们还给我介绍了新朋友,其中有些人已多次来访,一群人挤在一辆小巴士里前来。 他们讨论如何在今天的新加坡维系我们的社会主义理念与精神。

把我们的历史写成书面,让我们为自己的过去感到自豪,并帮助我们在经过数十年的沉默与孤独后重新团结。我们已经将自己整合为一个世代,这是仁贵一个非常贴切的用词。

华惹世代+

更重要的是,华惹世代不应局限于那些五十年代及六十年代初投身政治活动前线,并在内部安全法令下被捕入狱的人。我把自己这几十年来认识的年轻人,视为华惹世代+。他们以自己的方式坚持原则与立场,采取行动反对不公与剥削,对抗强大的现状。 我深信,无论前景怎么黯淡,总会有为了世俗的价值、正义与和平挺身而出,珍视我们的历史和共同愿景的新加坡人。这样的新加坡人,曾经有,下来继续会有。