by Teo Soh Lung

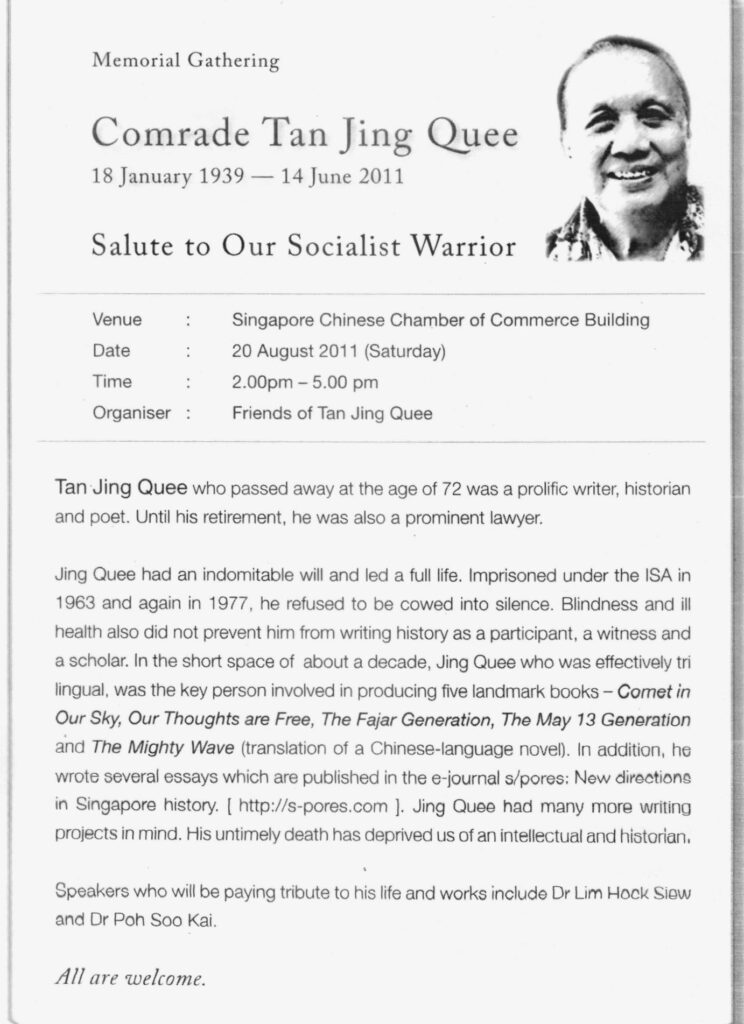

Tan Jing Quee who passed away 14 years ago today, is dearly missed by all his friends. Detained twice under the Internal Security Act (ISA), he was a man of many talents. An intellectual, writer, poet, lawyer and self-taught historian, he was a man with a mission to right the history of Singapore after his retirement from legal practice. He was in his 50s.

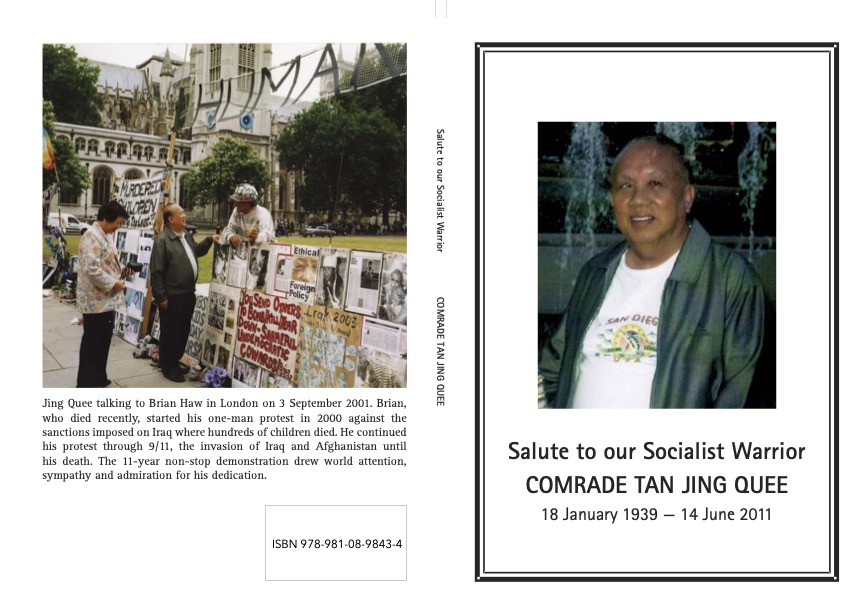

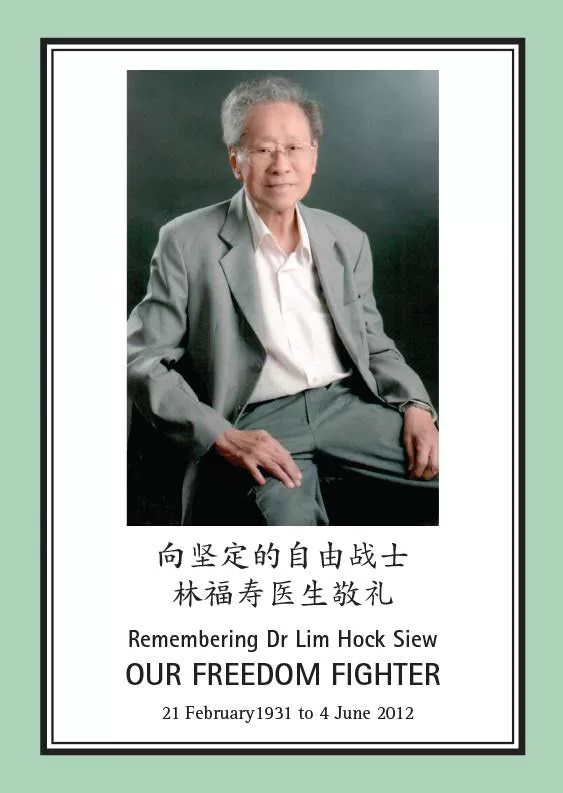

Jing Quee was an arts graduate from the University of Singapore. As an undergraduate, he was active in the University Socialist Club and was its president in 1961/62. He was also the editor of the undergraduate journal, FAJAR. According to the late Dr Lim Hock Siew, Jing Quee and a few others visited him a few weeks before Operation Coldstore to “discuss what they could do after our expected arrest. They were fully aware of their own arrests and detention should they take part in politics in that period but he displayed total determination to take up the challenge.”

On 2 February 1963, more than 100 people including Dr Lim Hock Siew were indeed arrested under the ISA. Fully aware that he too may be arrested if he did not take the conventional path of a university graduate, Jing Quee became a journalist for a short time and joined the trade union movement as a paid secretary of the Singapore Business Houses Employees’ Union upon his graduation. He went on to stand as a candidate for Barisan Sosialis in Kampong Glam in September 1963. He lost to the PAP incumbent, S Rajaratnam, the minister for culture by a mere 220 votes. Rajaratnam would have lost his seat had it not been for a third candidate who received 1200 votes.

Shortly after the election, the PAP took its revenge on their opponents by mounting Operation Pecah. Jing Quee and Wee Toon Lip, two Barisan candidates who lost narrowly at the election as well as three successful candidates, S.T. Bani, Lee Tee Tong and Loh Miaw Gong were arrested. Chan Sun Wing (Lee Kuan Yew’s former political secretary and Chinese tutor) and Wong Soon Fong who were also elected, left Singapore and became political exiles till the end of their lives.

Jing Quee was imprisoned for nearly three years. Upon his release, he left Singapore to study law at Lincoln’s Inn, London. He returned to Singapore, became a lawyer and raised his family. But he took a lot of interest in the future of Singapore. I recall he and some of his friends used to have regular meetings after office hours to discuss general issues . They even started a bookshop called Bunga Raya in Beach Road selling mainly socialist books. They also contemplated setting up a human rights committee. Although these activities were all legitimate, the PAP government arrested at least 22 people including most of the members of Jing Quee’s discussion group in 1977. Jing Quee therefore suffered a second detention and was severely tortured. He was released after three months.

Jing Quee was always interested in history and writing. Retiring from legal practice in his 50s, he embarked on a journey of meeting people who made history. According to the late G Raman, he even travelled to India to meet the first elected chief minister of Kerala, Namboodiripad. He also met Singapore’s exiles in Malaysia, UK, Thailand, China and Hong Kong. He made many friends, both young and old. He was an intellectual who never stopped learning.

In 1995, Jing Quee embarked on a two year Multi Disciplinary course at the Asia Pacific Studies, University of Leeds. He graduated with a Degree of Master of Arts in June 1997. Inspired by his lecturers like T.N. Harper, Greg Poulgrain and others, he and K.S. Jomo edited Comet in Our Sky, Lim Chin Siong in History in 2001. It was the first book about the freedom fighters of Singapore.

Jing Quee was a poet and had composed poems during and after his detentions. In 2004, he published his collection of poems, Love’s Travelogue, A Personal Poetry Collection. This was followed by another anthology titled, Our Thoughts Are Free, Poems and Prose on Imprisonment and Exile in 2009.

Jing Quee was a prolific writer. He was handicapped by his failing eyesight and cancer in later years. But he managed to edit and publish The Fajar Generation, The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore in 2010. This was swiftly followed with the publication of The May 13 Generation, The Chinese Middle Schools Student Movement and Singapore Politics in the 1950s in 2011. Jing Quee once told me that the May 13, 1954 incident when students from the Chinese Middle schools protested against compulsory national service contributed greatly to the British leaving Singapore.

Though Jing Quee was very ill after the publication of The May 13 Generation, he nevertheless embarked on a book launch tour to Kuala Lumpur, Penang and Johor. He spoke clearly and eloquently without notes at every launch. It was tremendous effort on his part but he was determined to do so. He was coherent and in high spirit. He enjoyed meeting all his comrades.

After the launch of The May 13 Generation, he went on to translate into English a Chinese novel, The Mighty Wave by He Jin. He was assisted by Hong Lysa and Loh Miaw Gong. Finally, Jing Quee published a delightful collection of short stories called The Chempaka Tree. He told me that he intended to write a play and that it was already all in his head. Unfortunately, he passed away without accomplishing this.

After the publication of the May 13 Generation, Jing Quee had plans to publish another serious book about Operation Coldstore. He knew he did not have the time. We are fortunate that The 1963 Operation Coldstore in Singapore, Commemorating 50 Years, edited by Poh Soo Kai, Tan Kok Fang and Hong Lysa was subsequently published and launched in 2014.

Jing Quee died at the age of 72. He had single-handedly placed the history of those who had initially fought alongside the PAP to gain independence from the British but who were compelled to leave the party and subsequently arrested and detained under the ISA or compelled to become political exiles. He had set the historical record straight. The PAP government have a lot to answer for what they did to their political opponents and intellectuals like Jing Quee and many others.

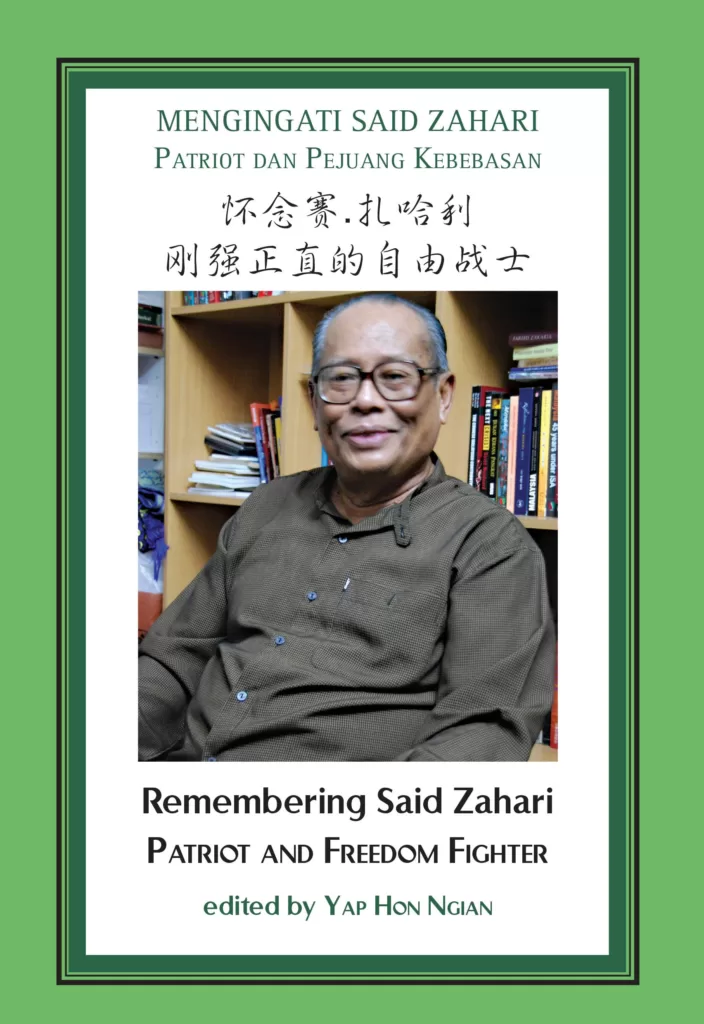

Function 8 have kindly made available the memorial booklets of Tan Jing Quee, Said Zahari and Lim Hock Siew at https://function8.sg/2025/06/13/three-memorial-books-download-and-read/